The Privacy Paradox

From data privacy to patient access: Hochul’s veto exposes a core tension in the digital age: the patient as a locus of rights, and the hospital as an operating system that must function under constraints that data can either facilitate or complicate.

In the arc of health care, data is not mere background noise; it is the quiet engine. It powers triage dashboards, informs predictive alerts, and shapes reimbursement models that depend on precise, timely data flows. Yet a patient’s private health information—historic diagnoses, genetic insights, treatment responses—remains the most intimate signal in that system. The veto, then, is less about a single policy choice than a morality play: how to house the patient’s dignity inside a digital infrastructure designed to optimize throughput, security, and cost control.

This is the paradox Hochul faced: lean against the operational frictions of a health system that treats data as both currency and care continuity, or lean toward broader privacy guarantees that can slow clinical decision-making, patient access, or even emergency response. The veto is heavy with consequences because it sits at the hinge between two trusted promises: privacy as a shield for the vulnerable, and data as a lever for timely, accurate care.

Policy Meets Practice

Consider the practical lines where policy meets practice. Hospitals operate across a continuum where consent forms are navigational aids, not mere bureaucratic hurdles. They must reconcile patient expectations with the reality that data access might depend on consent status, data-sharing agreements, and the risk calculus of cybersecurity threats. A veto that tightens privacy guardrails could improve patient control and reduce exposure to data breaches, but it could also slow down clinical workflows, complicate interstate referrals, and impede real-time analytics that inform critical decisions in mass-casualty or pandemic scenarios.

Information Asymmetries and Trust

This is where the discourse shifts from abstract rights to asymmetries of information. Patients increasingly demand transparency: who accessed their data, for what purpose, and for how long. Health systems, meanwhile, insist on operational visibility: who needs access, when, and under what protections. The conflict isn’t simply a dispute over consent forms; it is a dispute over the architecture of the health information ecosystem itself. If every data access event is audited with granular provenance, providers can reassure patients without paralyzing clinical urgency. If privacy rules are too permissive, the system risks blind spots in care continuity, identity verification, and error tracking.

Yet there is a third actor in this triad: the patient advocate who sees privacy not as a restraint but as a prerequisite for trust. Trust, in health care, correlates with outcomes equally as strongly as clinical protocols. When patients believe their data is guarded, they are more forthcoming about symptoms, family history, or risky social determinants. The veto, interpreted through this lens, becomes a nudge toward a privacy-by-design discipline—embedding consent choices into user-friendly interfaces, anonymizing data where feasible, and enabling patients to granularly determine who may “see” which slice of their health story.

Gradient Control and Tiered Approaches

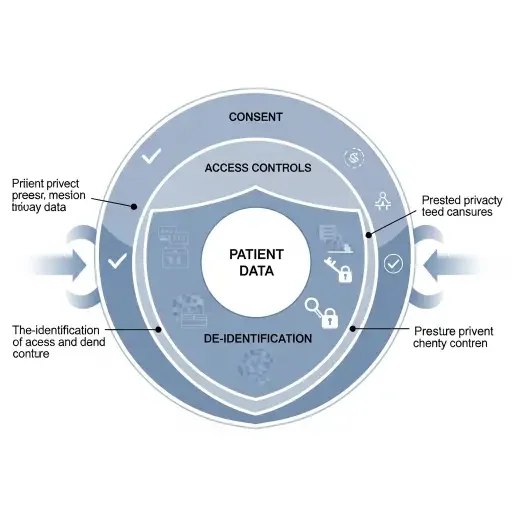

The policy question then becomes one of gradient control rather than binary choice. Rather than a sweeping expansion or reduction of access, a capability to calibrate protections by context could reconcile competing imperatives. For example, a tiered approach: routine administrative data governed by minimal consent; clinical data used in real-time for care delivery secured by robust authentication; de-identified data available for research under stringent governance. Such a spectrum preserves patient agency while preserving the operational tempo essential to modern care, especially in acute or transformative settings such as precision medicine.

The Political Calculus

The political calculus around veto power also matters. Vetoes carry signaling power—they communicate values to the public, to clinicians, and to investors who watch governance as closely as they watch margins. In the current moment, health systems are navigating volatility: staffing pressures, cyber threats, and the push toward value-based care that rewards outcomes and data stewardship in equal measure. A veto that articulates a principled stance on privacy can attract patient-advocacy alignments and push for stronger controls that do not sabotage care continuity. Conversely, a veto that tightens privacy without a credible path to secure, user-friendly data access risks alienating clinicians and eroding trust in public institutions.

To translate this complexity into a practical takeaway: the next era of health data policy will hinge on design. Design in policy terms means explicit, trackable data governance scores; design in clinical terms means front-line tools that clinicians trust and patients understand. Both require a shared language—one that reduces cognitive load via transparent provenance, contextual prompts, and opt-in clarity. The best reforms won’t merely lock data tighter or loosen it; they will reframe data as a shared resource with enforceable boundaries, patient sovereignty, and measurable safeguards.

The veto thus becomes a laboratory for a larger craft: how to wield policy as a patient-centered instrument without turning care into a bureaucratic labyrinth. The state’s duty is not just to protect privacy but to enable care that respects that privacy in the real world—where the emergency room, the pharmacy queue, and the remote-monitoring alert all share the same data bloodstream.

Governance Design in Practice

If the digital health era is a collective experiment, Hochul’s veto is an adaptive test of governance design. It suggests a future where patient rights are neither static nor abstract, but continuously renegotiated in labs of policy, software design, and clinical workflow. The humane outcome would be a health system that feels private enough to trust and fast enough to save—a system where cents and sensibilities align, not collide.

In the end, the patient’s right to know remains the north star. The operational realities—cybersecurity, interoperability, load-bearing data streams—chart the route. A well-calibrated veto could be the strategic adjustment that makes the path smoother: privacy that enables, not paralyzes; access that enables, not exploits; trust that endures beyond the last audit. The digital age, after all, is not merely about data—it is about dignity in how that data is requested, shared, and protected.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Policy documents, legislative analysis, interviews with health-system executives, privacy advocacy groups, and patient-rights advocates.