New York sued the U.S. Department of the Interior this week, challenging a departmental pause that has effectively frozen timelines for offshore wind leasing and approvals. The complaint centers on immediate harm: stalled project approvals, withheld needed federal authorizations, and a cascade of financing and contractual uncertainty that the state says threatens jobs, ratepayer planning, and its clean-energy targets. At the center of the dispute sits Empire Wind, the much‑watched project operated by Equinor that supplies a concrete example of how a procedural pause ripples through capital markets and construction schedules.

The Interior Department announced a temporary pause on certain offshore wind leasing timelines as part of a review of permitting processes and wider agency priorities. Washington framed the measure as a pause for policy reassessment—an administrative breathing space to consider environmental reviews and coordination with other federal agencies. New York’s suit frames the same action differently: as an unlawful suspension of agency duties that the state alleges exceeds statutory authority and causes quantifiable economic damage.

The complaint is precise about mechanics: the pause halts the progression of federal decisions tied to leases, conditional approvals, and construction permits. For Empire Wind, that means delays in obtaining final federal clearances for key project components—clearances that lenders and insurers treat as preconditions to disbursements and risk transfer. The state argues those interruptions increase financing costs and may trigger contractual penalties, pushing up the price of delivered power and undermining the predictable revenue streams underpinning investment.

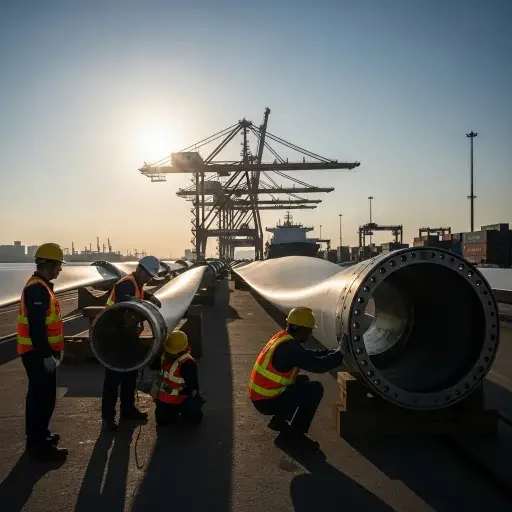

That transmission—from administrative pause to market pain—is not theoretical. Offshore wind projects are capital-intensive, with long lead times and tight scheduling windows for turbine delivery, port upgrades, and vessel charters. Lenders price in regulatory certainty; a sudden, open-ended interruption amplifies perceived regulatory risk—an input that raises the cost of capital. For developers, higher financing costs compress returns; for states and utilities, they can translate into higher rates or cancelled projects.

New York’s legal strategy is calibrated to force an expedited judicial review. The complaint asks the court to declare the pause unlawful and compel the Interior to resume its timelines or to justify, through transparent rulemaking, any changes in process. The state advances standing on both economic and regulatory grounds: harm to municipal planning and procurement, to contractors and workers currently in mobilization, and to ratepayers counting on future clean energy supply. The suit also highlights state federalism tensions—New York asserts a narrow injury to state prerogatives and policy goals that federal actors cannot lightly override.

The case strains against competing political narratives. Critics of rapid offshore leasing have argued for more cautious environmental review and for better coordination with fisheries and coastal communities. Proponents of accelerated deployment—state governments, unions, many utilities, and renewable developers—counter that pauses create precisely the harms regulators claim to prevent: investment stalls, domestic supply-chain opportunities wane, and geopolitical dependence on foreign energy persists. The litigation crystallizes those fault lines into a single procedural question with outsized material consequences.

For investors and corporate treasuries, the suit is an information event. It signals the degree to which subnational actors will use courts to police federal regulatory shifts that threaten local economic plans. A favorable ruling for New York would narrow administrative discretion in ways that reduce short-term regulatory tail-risk for projects like Empire Wind; an adverse ruling—or a prolonged back-and-forth—would extend uncertainty, prompting debt providers to impose wider spreads or defer lending decisions.

Equinor and other developers have publicly urged clarity rather than litigation. Their filings and statements emphasize the practical needs of supply contracts, vessel charters, and workforce scheduling. The industry’s message to capital markets is straightforward: predictability matters more than rhetorical assurances. For utilities and ratepayers, the calculus is equally immediate—delays change delivered-cost models and can push timelines for emissions reductions.

Legally, the case will hinge on statutory interpretation of the Interior’s authorities and the administrative record supporting the pause. Courts give agencies deference where policy judgments implicate technical expertise, but that deference is not limitless—procedural fairness and statutory bounds remain enforceable. If the court finds the agency failed to follow required notice-and-comment procedures or lacked statutory basis for a sweeping timeline suspension, the pause could be vacated or limited.

Politically, this fight will play in two arenas. In Washington, the agency can respond administratively—by narrowing the pause, issuing clarifying guidance, or initiating formal rulemaking that absorbs political heat but re-establishes predictable processes. In Albany and among regional stakeholders, the suit functions as leverage: it signals to developers, unions, and utilities that the state will aggressively defend projects it deems economically vital.

The stakes go beyond one project. Offshore wind is a cornerstone of many state decarbonization plans and a nascent industrial strategy—ports, shipyards, and turbine manufacturing are local economic opportunities. A sustained freeze will not only delay megawatts; it could slow the maturation of a domestic supply chain and the financing markets that serve it.

In short: the dispute compresses a wide policy debate into a binary legal test—did the Interior exceed its authority in pausing regulatory timelines, and if so, what remedy restores the equilibrium between rigorous review and investment certainty? For Empire Wind, the legal answer matters in days and weeks; for the sector, it may shape capital costs and deployment tempo for years.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

State court filing reviewed; Interior Department policy notices; public statements from Equinor, New York officials, and energy industry analysts.