Every acquisition does two things at once: it stitches technology into an acquirer’s product roadmap and it transfers people—locally concentrated expertise that rarely scales by engineering alone. Meta’s purchase of Manus, a boutique studio specialized in AI agents, follows that asymmetric logic. At face value the deal imports a set of agent architectures and prebuilt workflows into Meta’s product stack. Less obviously, it rewrites the constraint map: the bottleneck moves from raw model capacity to platform integration and the migration of talent who know how to turn models into persistent social agents.

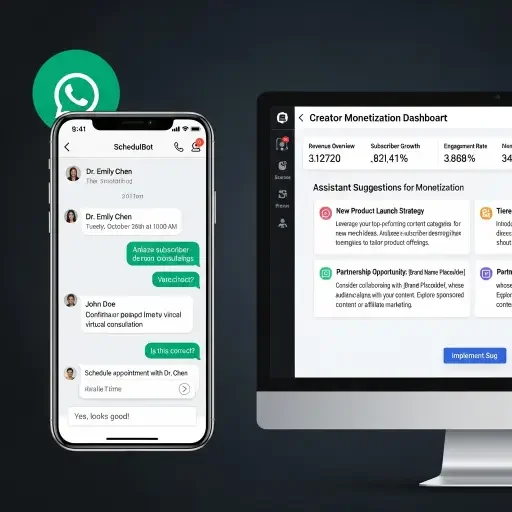

Meta gains three immediate practical advantages. First, Manus’ agent orchestration and memory primitives accelerate time‑to‑product: assistants that can maintain context, call APIs, and route multi‑step tasks through internal services require plumbing as much as models. Second, the acquisition bundles specialized datasets and fine‑tuning pipelines tuned for conversational persistence—data that is costly to re-create. Third, and importantly for Meta’s strategy, these agents map directly onto social surfaces (inbox threads, group chats, creator tools), lowering friction for mass deployment.

The consequence is structural: agents cease to be a standalone research problem and become a feature of Meta’s platform — a new set of APIs and UX affordances that other ecosystems must either match or reinterpret. That is why PLATFORM is the binding constraint here: if Meta can make agents a native capability of Facebook, Instagram, and WhatsApp, the company rewires user expectations and third‑party developer incentives around its standards and identity systems.

Rivals register the threat not just at the code layer but at the human layer. A focused studio like Manus is less about binary intellectual property and more about muscle memory—teams that have engineered dozens of agent lifecycles, learnt failure modes, and built monitoring practices for errant behavior. Talent migration is therefore a force multiplier: hiring Manus engineers gives Meta live operational knowledge, shortening iteration loops by months if not quarters.

Capital markets read the same ledger. Investors price acquisitions both for immediate synergies and for competitive signalling: who can assemble the largest team able to productize agents at scale? Expect follow‑on moves—strategic hires, targeted acqui‑hires, and an uptick in venture interest for tooling that bridges models and product surfaces. That puts CAPITAL as a second-order locus: where money flows, capability concentrates.

Two friction points will shape how durable Meta’s advantage is. First, integration risk. Agents are not widgets you paste into a feed. They require privacy design, latency budgets, safety layers, and monetization pathways that coexist with social norms. Second, regulatory attention. As agents become enmeshed in social experiences—recommending content, facilitating transactions, impersonating personas—regulators will ask whether bundling agents into dominant platforms raises competition or consumer‑protection concerns.

Regulators care about three questions that this acquisition surfaces. Does combining agent tooling with Meta’s social graph create exclusionary conduct—technical or contractual—that forecloses rival agent ecosystems? Are there data‑sharing practices embedded in the deal that amplify privacy risk by allowing persistent agent memories to access cross‑product signals? And finally, do talent consolidations materially lessen competition in this niche labor market, raising labor and innovation costs for startups?

Meta can defuse some concerns with design choices: open APIs, federated agent protocols, and clear data governance for agent memories. But those are strategic tradeoffs. Openness shrinks technical lock‑in and invites competitors; closed integration maximizes product advantage and draws regulatory scrutiny. The choice maps directly to corporate strategy: pursue platform dominance or cultivate an interoperable agent landscape.

For startups and incumbents outside Meta, there are practical counter‑strategies. They can double down on specialized vertical agents—financial planners, clinical assistants—where domain expertise and regulatory compliance are binding constraints that neutralize pure platform effects. Alternatively, they can focus on developer tooling and standards—middleware that lets any platform stitch models into products—turning the Manus playbook into a distributed commodity.

The acquisition also reframes the talent market. Expect more conditional offers tied to noncompete waivers, longer retention packages, and M&A as a talent acquisition instrument rather than a product one. For engineers, the calculus changes: joining a dominant platform yields reach and resources; staying independent preserves entrepreneurial optionality but raises the cost of competing at scale.

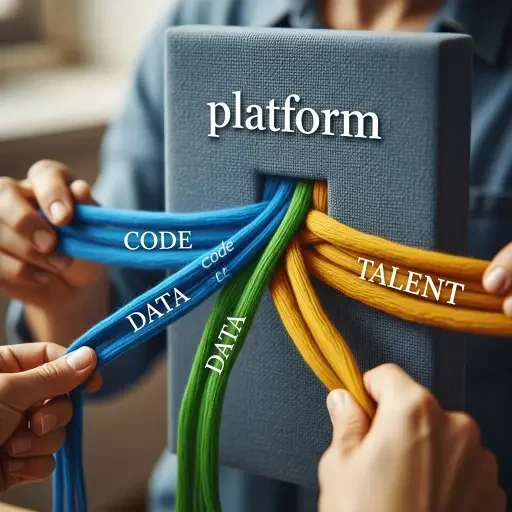

Meta’s Manus deal is not merely an IP purchase; it is a platform move that concentrates behavioral infrastructure—code, data, and the people who know how to run it—inside a social graph with billions of daily interactions. That concentration creates short‑term product velocity for Meta, a talent scramble for rivals, and a plausible regulatory storyline about platform power.

If you are a founder, investor, or regulator, act on one principle: distinguish between model innovation and product engineering. Models will keep advancing; the scarce commodity—at least for the next 12–24 months—is operational expertise that turns models into safe, context‑aware social agents. How that expertise is distributed will determine whether the next generation of social AI is centralized, federated, or law‑choked into narrow verticals.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Meta and Manus company announcements and acquisition disclosures; AI industry talent market analysis; regulatory statements from FTC and DOJ; tech industry reporting from The Information, TechCrunch, and The Verge.