The Mathematics of Mismatch

Over 1.1 million American jobs vanished in the first ten months of 2025—the fastest elimination cycle since the pandemic year of 2020. But raw numbers obscure the more unsettling pattern: AI-attributed dismissals reached 17,375 in nine months, with 7,000 occurring in September alone, suggesting an exponential acceleration rather than linear displacement. Meanwhile, AI agent capabilities double every seven months, while technical skills become obsolete in less than five years and displaced workers now spend an additional month or two finding roles requiring similar skills but different tools.

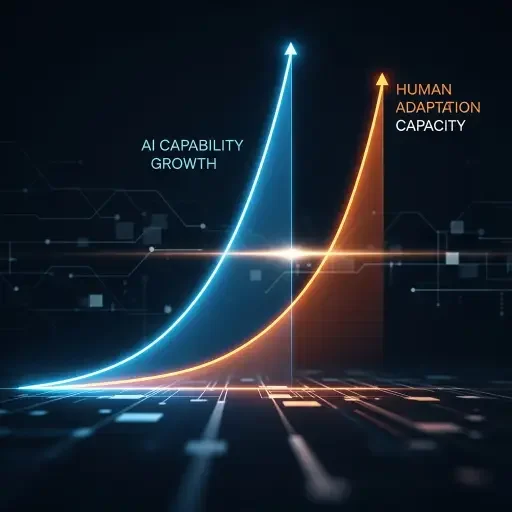

The velocity mismatch is entering dangerous territory. We’re witnessing not job loss, but temporal divergence—a widening gap between how fast machines evolve and how quickly humans can retool. This article maps that divergence, examines why official statistics mask its severity, and calculates when the asymptote becomes catastrophic.

I. The Signal Hidden in the Static

Begin with what seems like good news: Yale Budget Lab’s 2025 report found “no discernible disruption” in aggregate employment. The unemployment rate hovers near historic lows. Labor force participation remains stable. On the surface, the American job market appears resilient.

But aggregates lie through omission. Like viewing a forest from satellite altitude while missing that half the trees are dead—the canopy looks unchanged until the first strong wind.

October 2025 saw 153,074 job cuts announced, the highest October total in over twenty years. More revealing: this represents a 175% increase from October 2024. Yet these figures barely register in mainstream labor discourse, drowned out by aggregate stability signals. Three masking mechanisms explain the disconnect.

The Federal Fog: Government sector cuts reached 292,294 jobs by mid-2025, predominantly federal positions. The Department of Government Efficiency’s restructuring—the so-called “DOGE Impact”—created a statistical smokescreen. When one-third of announced layoffs stem from government consolidation, the private sector’s automation trajectory becomes invisible in the data noise. Courts greenlighting sweeping federal reductions affected not just direct government roles, but triggered downstream losses of 13,056 jobs in nonprofits and healthcare through funding cuts.

The Categorization Con: Here’s where semantics become destiny. Through July 2025, “technological updates” accounted for 20,219 job cuts, with another 10,375 explicitly attributed to AI—a semantic distinction without operational difference. IBM didn’t lay off 8,000 HR employees; it “modernized workflows using automation,” replacing them with an AI chatbot called AskHR. Disney didn’t eliminate hundreds of marketing positions; it implemented “automation” across divisions. Microsoft’s 15,000 cuts weren’t downsizing; CEO Satya Nadella explained that AI tools like GitHub Copilot now write 30 percent of new code, “reducing the need for layers of support teams”.

When displacement gets labeled “efficiency,” it vanishes from AI impact calculations. The true count sits somewhere between reported figures and reality’s darker mathematics—likely 3-4x higher than official AI-attributed numbers suggest.

The Lag-Indicator Blindness: Employment statistics photograph the past, not the trajectory. The dissimilarity index—measuring how far job distributions diverge from baseline—reached 0.26 by month 33 after AI’s breakout moment in late 2022. For comparison, computer adoption in the 1980s reached similar levels only after almost a decade, while internet-related shifts took roughly twice as long. The occupational landscape is rewiring faster than our measurement instruments can capture.

Consider this temporal quirk: unemployment among 20- to 30-year-olds in tech-exposed occupations has risen by almost 3 percentage points since early 2025, yet overall tech employment figures remain near pre-pandemic trends. The system isn’t contracting uniformly—it’s hollowing out from the bottom, severing the entry rungs while the upper ladders remain intact. Entry-level job postings have dropped 15% year over year, creating a generation locked out of career on-ramps while experienced professionals maintain their positions. For now.

When Shopify CEO Tobi Lütke tells staff “no more new hires if AI can do the job” and McKinsey deploys thousands of AI agents throughout the company, picking up tasks previously handled by junior workers, we’re not witnessing job loss—we’re watching the permanent elimination of entire career pathways.

The fog will lift, but only retroactively. By the time aggregate statistics confirm mass displacement, millions will have already spent years attempting to retrain for roles that no longer exist or have themselves become automation targets.

II. The Seven-Month Doubling and the Three-Year Retrain

Now we arrive at the mathematics that should concern anyone with a pulse and a paycheck.

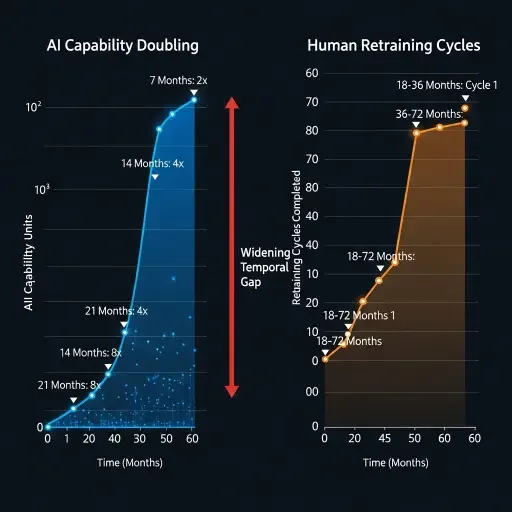

AI agent task-completion capabilities double every seven months. Not hardware power—task length. In 2019, leading AI systems could reliably handle tasks requiring about 10 minutes of focused work. By early 2025, that horizon expanded to approximately 24 hours of complex work. The pattern holds across 200 distinct tasks tested by METR researchers, from coding to general reasoning, with a correlation coefficient of R² = 0.83—about as robust as empirical trends get in technology forecasting.

More concerning: between 2024 and 2025, the doubling time compressed from seven months to just four months. We’re not on a steady exponential—we’re potentially on a super-exponential curve, where the rate of acceleration itself accelerates. If this compressed trend continues, AI systems could manage month-long complex projects by 2027.

Compare that velocity to human adaptation cycles.

Technical skills become obsolete in less than five years on average. But acquiring new technical competency—the kind that makes you employable, not just conversationally literate—requires substantially longer. Workforce retraining for technological shifts typically spans years, with skill needs changing every five to ten years. Community college certificate programs average 12-24 months. Short-term nondegree certificates taking less than a year tend to produce no or very small wage gains, meaning they don’t actually solve the displacement problem—they just burn time and tuition.

Let’s be generous and assume an 18-month retraining cycle—the lower bound for acquiring genuinely marketable skills in a new domain. During those 18 months, AI capabilities will double 2.6 times. A worker who starts retraining for a role that AI performs at, say, 30% efficiency will complete training to find AI performing that same role at 70-80% efficiency. The target moved while they ran toward it.

This isn’t like previous automation waves. Earlier decades saw computerization affect clear physical workflows; AI redefines mental ones, blurring boundaries between replacement and augmentation. You couldn’t retrain a steel mill worker to become a robot, but you could retrain them to operate different machinery or work in logistics. That pathway depended on a crucial factor: the new skill remained stable long enough to justify the investment.

AI demolishes that assumption. Skills needs will likely change every five to ten years—but that’s a conservative estimate based on historical patterns. Technical skills now become outdated in less than five years. If AI continues its current doubling trajectory, we’re looking at perpetual obsolescence: the career equivalent of running on a treadmill with accelerating speed, where simply maintaining position requires constant sprinting.

The World Economic Forum reports that only 11% of workers are currently “future-ready”—capable of excelling in uncertain environments and capitalizing on emerging opportunities. The other 89% face a grim calculation: invest 18-36 months retraining for roles that may not exist by the time training completes, or accept downward mobility into jobs AI hasn’t yet economically replaced—for now.

III. The Entry-Level Extinction Event

Start at the bottom, because that’s where the structure fails first.

Research from SignalFire shows Big Tech companies reduced new graduate hiring by 25% in 2024 compared to 2023. These aren’t hiring slowdowns tied to economic cycles. These are positions that no longer exist. In March, the unemployment rate for college-educated Americans ages 22 to 27 hit 5.8%, the highest level in four years—well above the national average, inverting the traditional education-as-insurance model.

The mechanism is brutally simple. Entry-level work involves routine tasks: collecting data, transcribing information, creating basic visualizations, learning organizational structures. Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei predicts AI could eliminate half of all entry-level white-collar jobs within five years. Not “disrupt”—eliminate. Bloomberg research reveals AI could replace 53% of market research analyst tasks and 67% of sales representative tasks, while managerial roles face only 9 to 21% automation risk.

This creates a structural impossibility: how do you reach management when the entry and mid-level rungs have been removed from the ladder?

At consulting giant McKinsey, thousands of AI agents have been deployed throughout the company, often picking up tasks previously handled by junior workers. At Duolingo, CEO Luis von Ahn uses “AI fluency” to determine who is hired and promoted—meaning the skill requirement isn’t domain expertise but the ability to effectively prompt and manage AI systems. Microsoft confirmed that 30% of company code is now AI-written, while simultaneously, over 40% of their recent layoffs targeted software engineers.

The irony is almost comedic: Microsoft vice presidents tell teams of 400 engineers to use AI for half their coding work, then lay off those same engineers months later. The engineers did exactly what management requested—optimizing themselves out of relevance.

But this isn’t just tech sector pathology. 81.6% of digital marketers already fear AI will replace content writers, and that fear is becoming reality as companies discover that “good enough” AI writing costs pennies compared to human salaries. HR departments face similar disruption—companies are discovering they can replace most HR workers with AI systems that work faster and cost less, with most companies forcing the change overnight and employees adapting when they realize they get instant answers 24/7.

The knock-on effects extend beyond individual careers. By 2030, 14% of employees globally will have been forced to change their career because of AI, with 20 million U.S. workers expected to retrain in new careers or AI use in the next three years. But retrain into what, exactly? While technical skills remain important, accounting for about 27 percent of in-demand skills, the majority of crucial skills are nontechnical—foundational skills like mathematics and active learning, social skills including social perceptiveness and negotiation, and thinking skills such as complex problem-solving and critical thinking together make up nearly 58 percent of skills needed in growing occupations.

The market is sending contradictory signals: automate technical work, but hire for “soft skills” that require years of professional context to develop—context you can’t acquire because entry-level positions no longer exist. It’s the employment equivalent of “we only hire candidates with five years of experience” for a technology that’s been publicly available for two years.

Around 18% of 20-year-olds made job-to-job transitions in a given year, but this drops to just 5% by age 60, and 2% for occupational changes. Mobility declines steeply with age, meaning older workers displaced by AI face increasingly difficult pivots into new roles. But younger workers can’t acquire the experience needed to reach those more secure positions. We’re engineering a deadlock: too experienced to be entry-level, too inexperienced for the only roles that remain.

IV. When Governments Notice the Building Is Already Burning

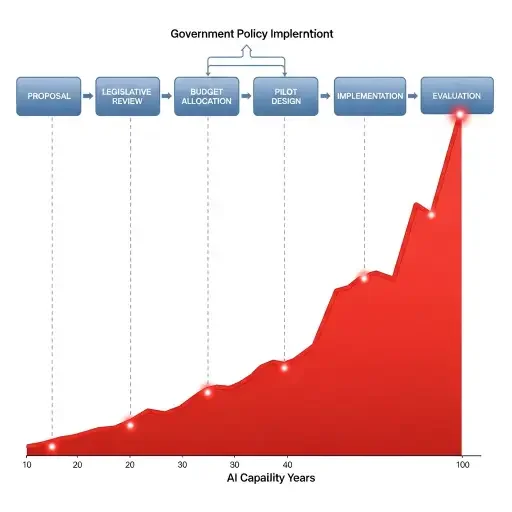

Policy response operates on legislative time, measured in years. Technology acceleration operates on Moore’s Law squared, measured in months. The divergence is structural.

The U.S. Departments of Labor, Commerce, and Education released their workforce development blueprint in August 2025, acknowledging that “AI represents a new frontier for workers” and that “the greatest workforce challenge of AI may be the speed of change itself”. The plan calls for creating regional AI learning networks, expanding registered apprenticeships, prioritizing AI literacy, and ensuring the workforce system can “adapt in real time” to shifting skill requirements.

The language is appropriately urgent. The timeline is fantasy.

The blueprint aims to “promote strategies that enable faster adjustment of training programs, quicker deployment of new models, and more responsive alignment to real-time labor market needs”—but it’s proposing to build responsiveness into systems that currently require Congressional authorization, state-level coordination, and multi-year grant cycles to implement modest changes. You can’t retrofit agility into bureaucratic architecture designed for stability.

Consider the practical constraints. The departments plan to “rapidly pilot new approaches” addressing worker displacement and shifting skill requirements for entry-level roles, with states and workforce intermediaries carrying out pilot programs. Pilots take 12-24 months to design, implement, and evaluate before scaling. By the time a pilot program proves effective, the skills it teaches may already be obsolete.

Short-term, nondegree certificates that take less than a year to complete tend to produce no or very small wage gains for individuals who complete them—yet policy interest in these certificates is growing despite uncertain returns. The impulse is understandable: do something fast. But speed without efficacy just burns resources. RAND researchers recommend proceeding with caution, emphasizing the need for rigorous experimental evaluations that include not just program completion rates but actual economic impacts on participants.

Meanwhile, nearly 48% of workers believe it is their employer’s responsibility to prepare them for the future of work, while only 20% view it as their own responsibility. But the World Economic Forum reveals a concerning stagnation in employer-led upskilling initiatives for the first time in three years. Companies cutting staff to boost quarterly earnings have little incentive to invest heavily in training workers who may be displaced in the next automation wave. The coordination problem is obvious: individual firms bear the full cost of training but capture only a fraction of the benefit if workers move to competitors. Without policy intervention forcing collective action, the market failure persists.

Recent federal initiatives, including $265 million in Strengthening Community Colleges Training Grants since 2021, demonstrate recognition of community colleges’ crucial role. But $265 million against nearly 50 million U.S. jobs at risk in coming years is rounding error, not strategy. If even 10% of at-risk workers need retraining at an average cost of $15,000 per person (a conservative estimate for effective mid-career reskilling), we’re looking at $75 billion—nearly 300 times current federal investment.

The math doesn’t work. The timeline doesn’t work. The institutional capacity doesn’t exist. And by the time it does, the problem will have metastasized beyond any policy intervention short of universal basic income—which AI researcher Geoffrey Hinton has dismissed as inadequate for addressing the loss of dignity and purpose tied to work.

V. The Asymptotic Divergence: Calculating the Point of No Return

Let’s put numbers to the dread.

Through July 2025, 10,375 job cuts were explicitly attributed to AI. Annualize that rate: roughly 17,800 per year. Now apply the observed acceleration: 7,000 AI-attributed dismissals occurred in September 2025 alone. If September represents the new baseline rather than an anomaly, we reach 84,000 AI-attributed dismissals annually. If the September rate itself accelerates proportionally to AI capability doubling (7-month cycle), we’re looking at 252,000 AI-attributed dismissals by end of 2026—a 1,350% increase from 2024 levels.

But recall: these are attributed dismissals only. The true count lies hidden in “technological updates,” “efficiency gains,” and “restructuring” categories. Apply a conservative 3x multiplier for misclassified automation displacement: 756,000 AI-driven job losses by late 2026.

Now layer in the capability curve. If AI agents reach month-long task horizons by 2027, vast swaths of middle-management and specialized professional work enter the automation window. 30% of current U.S. jobs could be fully automated by 2030, while 60% will see significant task-level changes due to AI integration. Not all task automation translates to job elimination—but significant task automation enables staff reduction through “efficiency.” A team of ten becomes a team of six. Six becomes four. Four becomes two specialists managing AI systems.

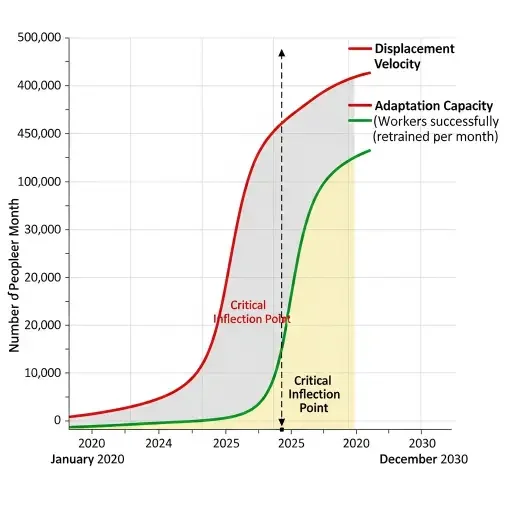

The asymptote emerges when displacement velocity exceeds adaptation capacity—when the rate of job obsolescence outpaces the rate at which workers can acquire new, stable skills. We’re approaching that threshold now.

The proportion of displaced workers remaining out of work for more than 27 weeks rose from 30.2 percent to 32.7 percent between 2022 and mid-2025. That’s a modest rise, but it signals friction in retraining. Workers whose previous tasks have been redefined by AI often take an extra month or two to reconnect with roles requiring similar skills but new tools. As AI sophistication increases, “similar skills but new tools” may become “fundamentally different skills using AI-augmented workflows”—a much steeper learning curve.

Consider the retraining pipeline as a queue. Workers enter at the displacement rate (input) and exit at the successful retraining rate (output). When input exceeds output, the queue grows—and with it, the duration of unemployment and the psychological toll of obsolescence. Currently, according to McKinsey, up to 375 million workers globally may need to switch occupational categories due to digitization, automation, and AI advancements by 2030. The U.S. represents roughly 4% of global population but 25% of global GDP—call it 15-20 million American workers needing occupational switches in the next five years.

20 million U.S. workers are expected to retrain in new careers or AI use in the next three years. That’s 6.7 million per year, or roughly 550,000 per month. Can the system absorb that? Employers announced just 488,077 planned hires through October 2025, down 35% from last year and the lowest since 2011. If hiring plans don’t accelerate dramatically—and they’re currently declining—then even successfully retrained workers face an absorption problem: nowhere to go.

This is the asymptote. Not mass unemployment measured in percentages, but structural dislocation measured in millions unable to find roles matching their skills, perpetually retraining for positions that evaporate before training completes, or accepting severe wage cuts into jobs AI hasn’t yet economically justified replacing.

Goldman Sachs Research estimates that if current AI use cases were expanded across the economy, just 2.5% of US employment would be at risk of displacement—but that’s based on current use cases, not capability curves. Goldman’s baseline assumption is 6-7% job displacement from AI, though displacement rates could vary from 3% to 14% under different assumptions. Even at the lower bound, 3% of 160 million employed Americans equals 4.8 million jobs—nearly the entire current unemployment figure. At the upper bound, 22.4 million jobs.

The Goldman analysis, however, assumes relatively stable AI capabilities during the transition period. They note that technology change tends to boost demand for workers in new occupations, taking place either directly through new jobs emerging from technological change or indirectly by triggering an overall boost in output and demand. That pattern held for previous automation waves because capability improvements were gradual. You had time to identify new jobs, design training, implement programs, and absorb displaced workers.

When capabilities double every seven months, that historical pattern breaks. The lag between “job eliminated” and “new job emerges requiring different skills” compresses beyond human adaptation speed. We get displacement without offsetting creation—not permanently, perhaps, but for a window measured in years. During that window, millions experience downward mobility, skill degradation, and the psychological damage of forced obsolescence.

This is not technological pessimism. It’s arithmetic.

VI. What Breaks When the Music Stops

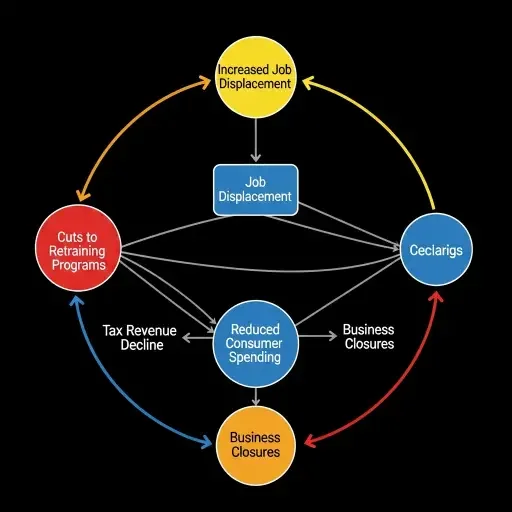

Economic dislocations produce second-order effects that dwarf the primary shock. The 2008 financial crisis destroyed $16 trillion in household wealth; the resulting political convulsions gave us Brexit, Trump’s first election, and populist surges across Western democracies. AI displacement won’t produce a single crisis moment—it produces rolling destabilization as successive cohorts realize their human capital has evaporated.

30% of U.S. workers fear their job will be replaced by AI or similar technology by 2025. Fear drives political behavior more reliably than rational self-interest. When 30% of the workforce believes they’re on borrowed time, you get demand for radical intervention: stop AI development, impose robot taxes, guarantee jobs regardless of productivity, implement UBI. Some of these are defensible policy positions; others are economic suicide. All become politically viable when enough people face immiseration.

In a study measuring public perception, those not affected by automation believed 29% had lost their jobs to automation, while those who were displaced estimated the rate at 47%—compared to an actual rate of approximately 14%. Perception shapes reality in politics. If voters believe AI has destroyed 30-40% of jobs when the real figure is 10-15%, policy responds to the perception, not the reality. You get ham-fisted interventions that neither address the actual problem nor calm the fear.

Consider also the generational fracture. Unemployment among 20- to 30-year-olds in tech-exposed occupations has risen by almost 3 percentage points since early 2025, while older workers in senior positions remain relatively insulated. Young college graduates face the worst conditions: the unemployment rate for college-educated Americans ages 22 to 27 hit 5.8% in March, the highest level in four years, even as the national rate sits at 4.2%. Education no longer functions as reliable insurance. A generation that followed the social contract—get educated, work hard, secure middle-class stability—finds the contract void.

That produces nihilism, not reform. Birth rates decline when young people can’t afford housing and see no stable career path. Mobility is closely linked to career development, wage growth, and job satisfaction, but as workers age, they may face health concerns, caregiving responsibilities, or simply a desire for roles better aligned with their values and life stage—without opportunities to retrain or transition into different roles, they risk being trapped in unsuitable jobs or exiting the workforce entirely. Exit from the workforce means exit from the tax base, which means less revenue for the retraining programs that might have prevented the exit. Doom loop.

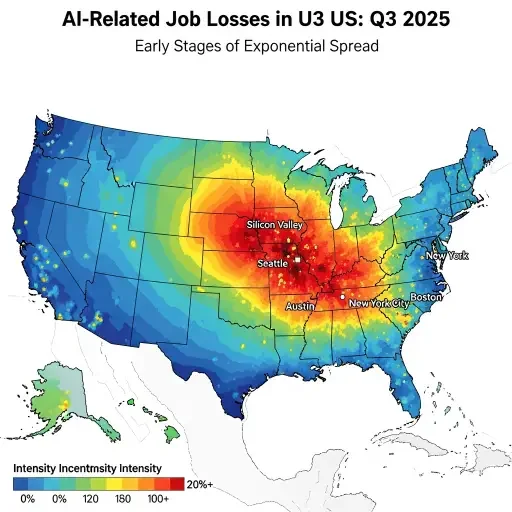

Then there’s the regional dimension. California’s Silicon Valley has lost over 11,000 jobs, Washington State saw more than 2,300 positions eliminated at Microsoft’s headquarters, and Texas lost over 14,000 workers from Tesla’s Austin operations. Tech hubs absorb the shock first, but displacement spreads as AI adoption diffuses across industries and geographies. Retailers announced more than 80,000 cuts through July 2025, up nearly 250% compared to the same period last year, driven partly by tariffs but also by automation in warehousing and customer service. Warehousing companies announced a staggering 47,878 cuts in October alone, representing a 4,700% month-over-month increase, as companies accelerate the shift to automated systems.

Rural and post-industrial regions lack the infrastructure to absorb displaced workers. Community colleges in these areas struggle with funding and faculty shortages. Community colleges emerge as pivotal institutions when integrated into robust regional ecosystems that include employers and intermediaries, but successful workforce development requires sustained investment and coordination. Where that coordination doesn’t exist—most of the country—displaced workers face either relocation (expensive, disruptive) or acceptance of lower-wage service jobs (economically catastrophic at scale).

The social compact fractures. Democratic legitimacy depends on citizens believing the system can deliver broadly shared prosperity, or at least a credible path toward it. When enough people conclude the system is rigged against them—not through corruption but through technological inevitability—they stop supporting the system. You get radicalization, populist demagogues promising impossible solutions, and political gridlock that prevents any functional response.

At some point, the question becomes: what’s the alternative to managed decline? Because if the market won’t provide employment and the political system can’t coordinate retraining at the required scale and speed, you’re left with either permanent dependency or letting millions fall through the cracks while pretending it’s their individual failure to “learn to code.”

VII. The Horizon Beyond the Asymptote

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: we might be wrong about all of this.

The World Economic Forum’s 2020 report predicted that 85 million jobs would be displaced while 97 million would be created by 2025, suggesting a net gain of 12 million jobs. That prediction assumed AI would follow the pattern of previous technological disruptions—destroy jobs in one sector, create jobs in another, with a lag period but eventual absorption. Perhaps it still will.

Goldman Sachs Research remains skeptical that AI will lead to large employment reductions over the next decade, noting that temporary unemployment caused by the adoption of labor-saving technologies typically increases the US jobless rate by 0.3 percentage point with every 1 percentage point gain in technology-driven productivity growth. Historical precedent suggests technological unemployment is transitory; new jobs emerge that we can’t currently imagine, just as “app developer” and “social media manager” didn’t exist two decades ago.

But historical precedent also assumed gradual capability growth. Previous automation waves took decades to unfold, providing time for labor markets to adjust. The current AI transformation marks the steepest occupational reshaping since systematic data began in the early 2000s, with the dissimilarity index reaching in 33 months what computer adoption took almost a decade to achieve. Speed matters. You can boil a frog gradually, but drop it in boiling water and you get a different outcome.

The optimistic scenario: technology change tends to boost demand for workers in new occupations, either directly through new jobs emerging from technological change or indirectly by triggering an overall boost in output and demand. AI doesn’t eliminate work—it transforms it. AI and data science specialists are among the fastest-growing job categories in 2025, with cybersecurity professionals in growing demand due to increased digital threats, showing a 32% growth in information security analyst jobs from 2022 to 2032. Healthcare roles like nurses, therapists, and aides are projected to grow as AI augments rather than replaces these jobs, with nurse practitioners projected to grow by 52% from 2023 to 2033.

Maybe the asymptote is an artifact of measurement. We count jobs destroyed but not yet the jobs created because they don’t fit existing occupational categories. The Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t have a checkbox for “AI prompt engineer” or “synthetic data curator” or “human-AI collaboration specialist.” The new economy emerges in the statistical shadows.

Or perhaps we’re underestimating human adaptability. Throughout history, people have proven remarkably resilient at finding new roles, new purposes, new ways to create value. The fact that we can’t imagine what those roles look like doesn’t mean they won’t exist. In 1900, 41% of Americans worked in agriculture; by 2000, it was 2%—yet we didn’t end up with 39% permanent unemployment. The economy restructured. Maybe it will again.

But there’s also a darker possibility, one that AI researchers themselves acknowledge: the displacement could be both faster and more comprehensive than any previous transition. Geoffrey Hinton, often called the “godfather of AI,” believes we’re heading toward a world where AI can do virtually any cognitive task a human can do, potentially within the next decade or two. When that happens, the question isn’t “which jobs remain?” but rather “what economic system makes sense when human labor becomes largely optional?”

That’s not a retraining problem. That’s a civilizational redesign problem.

VIII. The Velocity Problem Has No Velocity Solution

Return to the core mechanism: AI capabilities double every seven months. Human retraining takes 18-36 months. This isn’t a gap you close by making training more efficient. Even if you cut retraining time in half—an extraordinary feat—you’re still perpetually behind the capability curve.

The only solutions operate at a different logical level:

Slow down AI development. Politically infeasible and possibly counterproductive. The countries that impose strict limitations cede competitive advantage to those that don’t. China isn’t pausing AI research to let workers retrain. Neither is the EU, despite its regulatory posture. The U.S. certainly won’t. And even if all major powers coordinated—fantasy—the fundamental knowledge exists. You can’t uninvent calculus.

Accelerate human adaptation beyond biological limits. Brain-computer interfaces, cognitive enhancement, pharmaceutical augmentation—all theoretical, all years away from safe deployment at scale, all raising ethical questions that make AI displacement look simple by comparison. You don’t solve technological disruption by turning humans into cyborgs, at least not in the relevant timeframe.

Restructure economic distribution. If human labor becomes partially or fully optional, the link between work and income breaks. Universal Basic Income, negative income taxes, sovereign wealth funds distributing automation dividends—these address income but not purpose. Humans derive meaning from productive contribution. Strip that away and you get social pathology at scale, what Hinton warns about regarding dignity and purpose tied to work. Unless we’re prepared to fundamentally reimagine what gives life meaning beyond market economics—a cultural shift that typically takes generations—this path leads to widespread demoralization even if material needs are met.

Accept managed decline in labor force participation. Let millions exit the workforce, supported by transfer payments and early retirement, while the remaining employed population works alongside AI systems. This is the path of least resistance, which means it’s probably the path we’ll take by default. It avoids both the impossibility of retraining at velocity and the political difficulty of radical economic redesign. But it produces a two-tier society: those who successfully adapted or were lucky enough to have skills AI can’t yet replicate, and everyone else. That breeds resentment, political instability, and eventually, systemic crisis.

None of these solutions are satisfying. All of them require coordination at scales we’ve rarely achieved outside of wartime mobilization. And unlike war, which produces unifying threat perception, AI displacement appears gradual—until suddenly it’s everywhere, and by then, the capacity for coordinated response has eroded.

The uncomfortable answer is that there probably isn’t a “solution” in the traditional sense—no policy intervention that prevents disruption while preserving current economic structures. What we’re experiencing is a phase transition, like water becoming steam. You can’t solve steam. You can only adapt to its properties or get scalded.

The question then becomes: how do we design institutions resilient enough to survive the transition without collapse? Because the alternative—letting markets and politics battle it out in real-time while millions experience downward mobility—produces outcomes nobody wants. Not the displaced workers, obviously. Not the companies, who need functional societies to sell products into. Not the governments, who face legitimacy crises when they can’t deliver broadly shared prosperity.

We need, in effect, to build the parachute while falling. The ground is approaching, the velocity is increasing, and we’re still arguing about parachute design specifications.

IX. The Signal in the September Spike

Return to that September 2025 data point: 7,000 AI-attributed job dismissals in a single month. Why does this matter beyond the arithmetic?

Because exponential curves look linear until they don’t. For months or even years, the numbers seem manageable, incremental, just another economic adjustment. Then you hit the inflection point—the elbow of the hockey stick—and suddenly the scale overwhelms the system’s absorption capacity.

September might be noise. A statistical blip, one outlier month that regresses to the mean in October and November. But if it’s signal—if 7,000 per month becomes the new baseline and continues accelerating proportionally to AI capability growth—then we’ve already crossed the inflection point. The disruption isn’t coming; it’s here. We’re just experiencing it with the lag inherent to all large-scale social phenomena.

Major economic shifts don’t announce themselves with sirens. The 2008 housing bubble was obvious in retrospect but vigorously denied by experts as it inflated. The 2020 pandemic economic collapse seemed sudden but resulted from months of ignored warnings. The dot-com crash, the 1970s stagflation, the Great Depression—all had leading indicators that were visible to anyone paying attention, yet institutional response came late if at all.

AI displacement follows the same pattern. The signals exist: entry-level hiring cratering, unemployment duration rising, regional clusters of tech-sector cuts, companies explicitly replacing workers with automation, governments acknowledging they don’t know how to retrain workers fast enough. But aggregate statistics still look acceptable, so we treat it as a future problem.

The future problem is a present problem moving at exponential velocity. By the time it’s undeniable in the aggregate data, millions will have already fallen through the gaps between “we should do something” and “we are doing something” and “something is actually working.”

This is the core insight: displacement velocity creates a visibility lag. The full scale becomes apparent only after the crisis has metastasized beyond easy intervention. It’s like watching a fire spread in slow motion through a building while debating the optimal placement of fire extinguishers—by the time you finish the debate, you need the fire department, and by the time the fire department arrives, you need bulldozers to contain the collapse.

We can track the proxy indicators: venture capital funding flowing toward AI-automation companies, increasing mentions of “AI” in corporate earnings calls paired with headcount reduction announcements, the ratio of AI specialists hired versus general workers, even linguistic shifts in job postings requiring “AI fluency” as baseline qualification. Each indicator shows acceleration. None of them appear in official employment statistics until quarters later.

The September spike, if confirmed by subsequent months, marks the moment when displacement velocity exceeded the threshold of public visibility. Not full visibility—most people still aren’t tracking Challenger Gray & Christmas reports or parsing Bureau of Labor Statistics category changes. But enough visibility that journalists start writing trend pieces, politicians start receiving constituent complaints, and companies start facing public pressure to address worker displacement.

That visibility creates political forcing functions. Once the problem registers at scale, policy response becomes mandatory, even if that response is ineffective. We’re likely about to witness a rapid proliferation of workforce retraining initiatives, AI impact studies, blue-ribbon commissions, and Congressional hearings—all the institutional machinery of “doing something” without necessarily solving anything.

The tragedy is that we had time to prepare. AI capabilities have been on exponential trajectories since at least 2019. The GPT series, DALL-E, AlphaGo, GitHub Copilot—each advance was public, documented, and extrapolatable. Researchers published papers on capability doubling times. Companies broadcast their automation intentions. The information existed; we just treated it as science fiction until it arrived as economic reality.

Now we’re in reactive mode, always one step behind the acceleration curve, proposing eighteen-month retraining programs for skills that will be obsolete in seven months, designing institutions for gradual change in an era of explosive transformation.

The September spike is the sound of the future arriving ahead of schedule. Whether it’s a harbinger or an anomaly, we’ll know within months. If October and November show similar or increasing figures, we’re watching the inflection point in real-time. If they revert to trend, we have a bit more time—though how much is anyone’s guess.

Either way, the velocity problem persists. AI capabilities aren’t slowing down. Human biology isn’t speeding up. The math doesn’t change based on our preparedness or lack thereof. The asymptotic divergence continues.

X. What We Do When There’s Nothing to Do

We arrive at the hardest question: what does responsible action look like when the problem may be structurally unsolvable?

The temptation is paralysis. If retraining can’t keep pace, policy can’t adapt quickly enough, and economic restructuring is politically infeasible, why bother? Just ride the wave and hope you’re not among those displaced. That’s a rational individual response. It’s catastrophic as collective strategy.

The alternative is imperfect action—interventions that don’t solve the problem but reduce harm at the margins, buy time, build institutional capacity for when political will finally catches up to reality.

Near-term pragmatism: Expand community college funding immediately. Not because short-term certificates produce great outcomes—they often don’t—but because community colleges are the only institutions positioned to deliver fast, locally-adapted training at scale. Focus funding on programs with proven track records: healthcare, skilled trades, specialized technical fields AI hasn’t yet economically replaced. Meanwhile, aggressively research which training approaches actually produce employment gains, using rigorous experimental evaluations rather than hopeful guesses. Kill ineffective programs fast; scale effective ones faster.

Medium-term infrastructure: Create portable benefits systems that aren’t tied to specific employers. If workers will change jobs every 3-5 years—and change occupations multiple times across a career—then healthcare, retirement, and unemployment insurance need to follow the worker, not the position. Singapore’s SkillsFuture program provides lifelong learning credits; France has personal training accounts that accumulate regardless of employer. Neither is perfect, but both acknowledge that the employer-employee social contract is dissolving.

Long-term cultural shift: Start normalizing career discontinuity. The idea that you choose a path at 22 and follow it until 65 is already dead; we just haven’t held the funeral. Instead of treating career changes as failures, build systems that expect and support them. That means retraining without stigma, financial support during transitions, and recognition that becoming obsolete isn’t a personal failing—it’s a systemic inevitability in an era of exponential technological change.

None of this prevents the asymptotic divergence. These are sandbags against a flood, not a dam. But sandbags matter when the alternative is uncontrolled inundation.

The deeper question—the one we keep avoiding—is whether we’re willing to fundamentally reimagine the relationship between work and worth. If AI can do most cognitive labor, and robotics eventually handles most physical labor, what’s the point of human economic contribution? Not the point of human existence—that’s philosophy—but the point of the economic system that currently structures human existence.

Markets allocate resources efficiently when scarcity exists and human labor adds value. When neither condition holds—when production becomes abundant due to automation and human labor becomes optional—markets break. Not in the sense of crashing, but in the sense of no longer serving their social function of broadly distributing prosperity in exchange for contribution.

You can patch that with UBI or guaranteed employment or some hybrid system. But patches don’t address the underlying meaning crisis. If you’re not economically necessary, what are you? A consumer? A hobbyist? A ward of the state? These aren’t just policy questions—they’re existential ones.

The uncomfortable truth is we probably won’t answer these questions proactively. Societies don’t tend to redesign their fundamental structures until forced by crisis. We’ll stumble toward solutions reactively, improvising responses as each wave of displacement hits, probably landing somewhere between managed decline and haphazard UBI, with significant human suffering along the way.

That’s not defeatism. It’s pattern recognition. We know how humans respond to large-scale, slow-moving threats that require coordinated action and sacrifice of short-term interests. We’re living through climate change, which exhibits many of the same coordination failures. AI displacement is faster but follows similar dynamics: visible signals, institutional inertia, political paralysis, eventual crisis forcing suboptimal compromise.

The best we can do—individually and institutionally—is reduce the severity of the eventual collision. That means building resilience into systems now, creating redundancy and capacity that seems excessive in stable times but proves essential during transitions. It means being honest about the scale and velocity of what’s coming rather than pretending solvable problems exist where they don’t. And it means accepting that this is a crisis we’ll muddle through rather than solve, hopefully with enough grace and mutual support to preserve social cohesion.

Because the alternative—ignoring the asymptotic divergence until it produces mass immiseration and political collapse—isn’t a choice. It’s suicide by denial.

Coda: The Recursive Compression

The automation displacement velocity is accelerating beyond human adaptation capacity. AI capabilities double every seven months; humans retrain in 18-36 months. This velocity mismatch creates asymptotic divergence—a widening gap between technological change and human response that no policy, at current coordination levels, can close. The September 2025 spike in AI-attributed dismissals (7,000 in one month) suggests we’ve reached the inflection point where exponential growth becomes visible, though official statistics lag by quarters or years, masked by categorization games and aggregate stability.

Think of it as two trains on converging tracks, one accelerating exponentially, the other moving at fixed human speed. The collision is mathematical inevitability, not pessimistic prediction. We can’t prevent it. We can only reduce the impact: build better cushioning through portable benefits and flexible training, accept that career discontinuity is now permanent, and acknowledge that when AI can do most cognitive work, the entire premise of market-based economic value distribution requires fundamental rethinking.

The actionable principle: prepare for discontinuity, not stability. Build systems that expect disruption, support transitions rather than prevent them, and recognize that in an age of exponential technological velocity, resilience matters more than optimization. The ground is approaching. Whether we build parachutes or argue about engineering specifications determines whether we land or crater.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Analysis based on Challenger Gray & Christmas job dismissal data, Yale Budget Lab employment studies, METR AI capability research, U.S. Departments of Labor/Commerce/Education workforce reports, Goldman Sachs and McKinsey economic forecasting, World Economic Forum workforce projections, and federal employment statistics through November 2025.