The detail that changes everything is timing.

This wasn’t a box lifted from a porch after delivery—the familiar crime of opportunity that Amazon has trained us to expect. There was no doorbell ring. No blurry confirmation photo of groceries wedged against a screen door. No hurried driver already halfway down the block when the notification arrived. The $300 Walmart grocery order was intercepted before arrival, siphoned out of the delivery chain itself, somewhere between warehouse checkout and final mile.

The manager’s phone call came hours later, not to apologize but to investigate: Did you receive it? That question—procedural, uncertain, oddly hollow—captures something larger than a single logistics failure. It marks a shift from isolated crime to systemic leakage, where economic pressure no longer waits for packages to land on porches. When theft moves upstream into the supply chain itself, it suggests not opportunism but necessity, not impulse but structure adapting to stress.

This is what a K-shaped economy looks like at street level. Not in employment statistics or stock charts, but in the quiet erosion of systems that once felt reliable. The groceries never arriving is the economic story, not an aberration from it.

Where Systems Fail First

Economists often insist that anecdotes are not data. But systems fail first in anecdotes, long before the aggregate indicators catch up. A K-shaped economy does not announce itself cleanly in GDP tables or Federal Reserve reports. It appears in missing groceries, in delivery drivers who vanish from the chain mid-route, in corporate managers calling to ask questions they already know the answer to. These are early-warning signals—the kind sociologists and anthropologists notice while economists wait for the quarterly revisions.

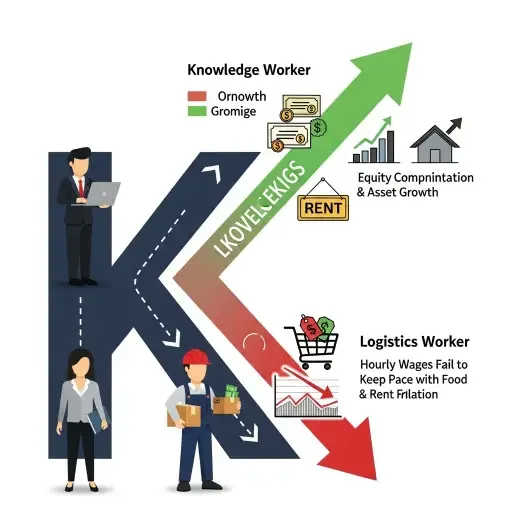

At the top of the K, capital is liquid, mobile, abstract. Wealth accumulates through asset appreciation—stocks, real estate, private equity stakes that compound without requiring physical presence or daily labor. At the bottom, everything is physical: food, fuel, rent, time. Pressure accumulates precisely where substitution is impossible. You cannot hedge groceries. You cannot diversify your way out of needing to eat.

When a delivery network begins leaking inventory before customers receive it, the problem is not logistical incompetence. The problem is that the economic stress experienced by workers inside that system has exceeded the friction costs of enforcement. Someone calculated—consciously or not—that the risk of taking $300 worth of food was lower than the certainty of not having enough money for their own groceries. This is rational behavior inside an irrational structure.

The Labor Market That Generates Work Without Margin

Officially, jobs still exist. The unemployment rate hovers below 4%, a level that would have seemed impossible a decade ago. Help wanted signs still appear in windows. Gig platforms still dispatch workers to deliver, drive, assemble, and haul. But the composition has shifted in ways that aggregate employment data obscures.

The economy has generated work without reliably generating margin—margin for workers, margin for error, margin for dignity. Lower-wage logistics and gig-adjacent roles have absorbed much of the labor demand created by e-commerce’s expansion, but real wage growth for these workers has consistently lagged inflation in essentials. When food prices rise 25% over three years and your hourly rate increases 8%, the math stops working. Theft migrates from opportunistic to rational. The system begins to leak calories.

This is how a K-shaped labor market manifests at ground level. High-skill workers see compensation increasingly tied to assets and equity—stock options, RSUs, profit-sharing tied to market performance. Their wealth grows while they sleep. Low-skill workers see compensation tied to hours and volatility—shifts that can be canceled, tips that fluctuate, piece rates that compress when demand softens. The distance between these two realities widens silently, transaction by transaction, delivery by delivery.

A delivery driver making $16 per hour in a market where studio apartments start at $1,800 and a week’s worth of groceries costs $150 is not participating in the same economy as the customer ordering those groceries from a home office between Zoom calls. They occupy the same geography but exist in parallel financial universes. When the strain becomes unsustainable, something has to give. Often, it’s the inventory.

Capital Floats While Infrastructure Erodes

Meanwhile, equity markets remain buoyant. Major indexes hover near all-time highs, led by firms with pricing power, automation leverage, and minimal exposure to labor volatility. Investors are not irrational here—they are allocating capital toward insulation. Companies that can replace workers with software, that can pass costs to consumers, that operate in oligopolistic markets with moats, these are the ones that thrive in a K-shaped environment.

But insulation has a shadow effect. As capital concentrates at the top, floating upward into asset valuations and shareholder returns, the cost of maintaining everyday systems is pushed downward onto workers least able to absorb shocks. Delivery networks, retail enforcement, and service reliability degrade not because of incompetence, but because resilience has been priced out of the system.

Walmart, Amazon, and other logistics-dependent retailers operate on margins thin enough that investing heavily in theft prevention at the worker level would erode profitability. It’s cheaper to refund or replace missing orders than to implement the kind of surveillance and accountability systems that would catch internal diversion. The calculation is coldly rational: a certain percentage of shrinkage is simply the cost of doing business in a stressed labor market.

The customer receives a polite apology and a refund. The manager makes a perfunctory call. The system absorbs the loss and moves on. But the loss is not absorbed evenly—it’s externalized onto the next customer who has to wait longer, onto the next worker whose route gets audited more aggressively, onto the broader social fabric that erodes slightly with each unresolved incident.

When Reliability Becomes Tiered

In a healthier economy, logistics are invisible and boring. Food arrives when the app says it will. Receipts reconcile. The system absorbs friction without making users aware of its internal mechanics. In a stressed economy, reliability itself becomes stratified—another dimension along which inequality expresses itself.

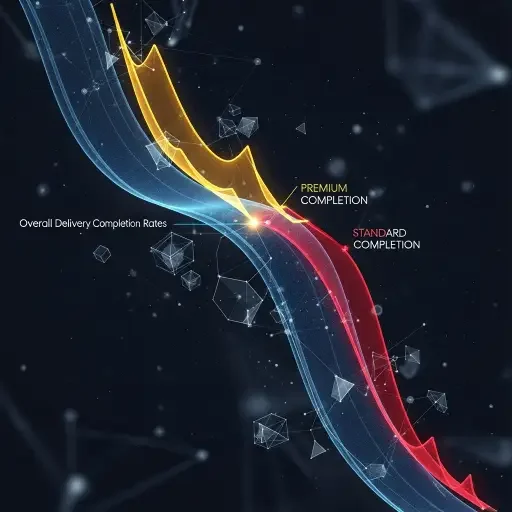

Affluent households respond to unreliability by substituting up: premium delivery services with live tracking and signature confirmation, gated communities with controlled access, subscription models that guarantee priority fulfillment. These households experience an economy where nothing breaks, where systems work as promised, where the friction of daily life remains manageable.

Everyone else absorbs loss. They file refund claims. They make extra trips to physical stores. They adjust their expectations downward, learning to anticipate failure as the default rather than the exception. The K-shape hardens—not just in income, but in predictability. Some Americans live in an economy where the future is legible and systems are responsive. Others live where nothing quite holds, where every transaction carries downside risk that cannot be hedged.

The theft before arrival is not chaos. It is adaptation—the system finding a new equilibrium at a lower level of trust and functionality. This is what happens when economic stress exceeds the capacity of existing institutions to manage it. Norms erode not because people suddenly become immoral, but because the cost of adhering to norms exceeds the cost of violating them.

What the Missing Groceries Signal

If you wanted to design an indicator that captured the lived reality of a K-shaped economy, you could do worse than “percentage of deliveries that never arrive.” It’s a metric that sits at the intersection of labor stress, consumer strain, corporate cost-cutting, and enforcement breakdown. It measures the point where systems begin to leak under pressure.

standard service tiers, against backdrop of rising inequality metrics.

Traditional economic indicators miss this entirely. GDP continues to grow because the refunded order still counts as consumption. Employment statistics remain healthy because the driver who diverted the groceries is still counted as employed. Corporate earnings hold up because the shrinkage is built into margin guidance. But something fundamental has broken—the basic social contract that says if you order food and pay for it, the food will arrive.

This breakdown is not uniformly distributed. It concentrates in lower-income neighborhoods, among non-premium delivery tiers, in the interactions between stressed workers and stressed customers. The top of the K experiences a different economy entirely—one where Whole Foods deliveries arrive within the scheduled two-hour window, where customer service responds within minutes, where problems get resolved with minimal friction.

The manager’s question—Did you receive it?—becomes diagnostic. It reveals an organization that has lost confidence in its own logistics, that must now verify at the individual transaction level what should be systematically guaranteed. When a retailer has to ask customers whether delivery actually happened, the system has moved from reliable to probabilistic.

The Quiet Unraveling

What this moment reveals is not moral collapse but economic signaling. When essential goods are diverted before reaching their destination, it tells us where pressure is highest and enforcement weakest. It tells us which layers of the economy are load-bearing and which are cracking under strain that has been building for years.

A K-shaped economy doesn’t just produce inequality in wealth or income. It produces different realities, operating on the same street, shopping from the same retailers, using the same infrastructure. One reality is insulated, predictable, and responsive. The other is precarious, unreliable, and extractive. The distance between them grows not through dramatic events but through accumulation—through a thousand missing deliveries, canceled shifts, denied claims, and unanswered questions.

The theft of groceries before delivery is a small incident. It affects one household, costs one company a few hundred dollars in refunds, occupies a few minutes of a manager’s time. But it has diagnostic power beyond its scale. It shows us where the economic stress is concentrating, how systems respond when pushed past their design limits, and what happens when the gap between top and bottom becomes wide enough that different rules apply to different participants.

Sometimes the clearest economic indicator isn’t a chart or a forecast or a revised GDP estimate. Sometimes it’s a phone call from a store manager asking whether the groceries ever made it—when everyone involved already knows they didn’t, and everyone understands exactly why.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Analysis drawing on Federal Reserve labor data, gig economy wage reports, consumer stress indicators, and delivery logistics industry trends