The tech industry eliminated 25,000 jobs in January 2026, extending a multi-year contraction that has now erased over 400,000 positions since early 2023. Oracle is planning another 30,000 cuts to fund data center expansion. Amazon just announced 16,000 layoffs on top of 14,000 from late 2025. Meta reduced Reality Labs by 1,500 workers—10% of the division. The pattern is consistent: companies are shedding headcount while simultaneously increasing capital expenditure on AI infrastructure. What’s changed is the target demographic. The layoffs are no longer concentrated at the entry level, where automation has historically displaced repetitive task workers. They’re moving up the org chart into middle management, project coordination, and specialized knowledge roles—positions that require judgment, context, and institutional memory. And according to a Resume.org survey of 1,000 U.S. hiring managers, 55% expect layoffs in 2026, with 44% identifying AI as the primary driver.

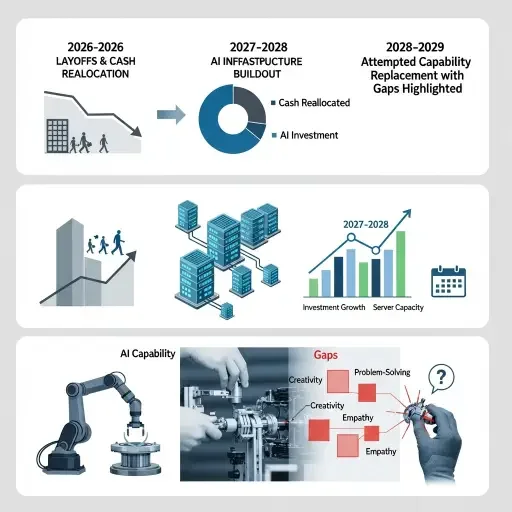

The framing is deliberate: executives are calling these “AI-driven efficiencies” rather than cost-cutting. But a Forrester Research report reveals the mechanism’s absurdity. Fifty-five percent of employers now admit they regret AI-attributed layoffs from 2025. Many laid off workers for AI capabilities that didn’t exist yet—betting on future automation rather than deploying functional tools. The result is a temporal arbitrage: companies are destroying organizational capacity now to fund the infrastructure they hope will replace it later. The bet assumes that the knowledge embedded in a mid-level program manager, customer success lead, or technical account executive can be extracted, codified, and reconstituted as an agentic AI system. It rarely can.

The Agentic AI Promise and the Capability Gap

Agentic AI—systems that can autonomously pursue goals, make decisions across multiple steps, and adapt to changing contexts—represents the theoretical basis for this wave of displacement. Unlike earlier automation, which excelled at narrow, repetitive tasks, agentic systems are supposed to handle ambiguity. They should manage projects, negotiate with stakeholders, synthesize conflicting information, and execute strategic priorities without constant human oversight. That’s the vision. The reality is messier.

Current AI systems, even frontier models, struggle with tasks that mid-level employees handle routinely: maintaining context across weeks-long projects, navigating organizational politics, detecting when stakeholders are misaligned, understanding what’s been left unsaid in a meeting. These are not technical challenges amenable to scaling compute. They’re problems of embedded knowledge—the kind that accumulates through years of navigating a specific organization’s idiosyncrasies. When you fire a program manager with seven years of institutional context, you don’t just lose her labor. You lose the illegible knowledge of which engineers can actually ship on deadline, which executives need pre-meeting socializing, which vendors will negotiate off-contract.

Companies are discovering this through forced experimentation. Klarna replaced 700 customer service employees with AI, then had to rehire humans when quality collapsed and customers revolted. Amazon’s “Just Walk Out” retail technology, marketed as AI-powered, actually relied on remote workers in India watching camera feeds—the automation was theater. Forrester predicts that half of AI-attributed layoffs will result in quiet rehiring, often offshore or at significantly lower salaries. The pattern reveals the actual mechanism: AI isn’t replacing mid-level work; it’s being used as political cover for labor arbitrage and permanent headcount reduction.

Who Actually Gets Displaced

The Stanford study that Deutsche Bank cited found a 16% relative decline in employment for recent graduates in AI-exposed roles. But the data shows the exposure isn’t uniform. Entry-level positions in customer service, basic coding, and routine analysis are indeed contracting. Yet the faster-growing displacement category is mid-career knowledge workers in roles that require coordination, synthesis, and judgment. These are positions where AI tools augment productivity for those who remain but justify eliminating the roles entirely for those who are cut.

Consider the program manager archetype: someone who doesn’t write code or close deals but ensures that engineering, sales, and product teams stay aligned through a product launch. The labor is invisible until it’s missing. When companies remove these roles and attempt to replace them with workflow automation tools or AI assistants, what collapses isn’t the explicit work—the meeting scheduling, the status updates—but the tacit coordination. The engineer who used to get a heads-up that legal was raising concerns, the sales rep who used to learn that product was slipping the roadmap, the executive who used to receive pre-filtered escalations—all of them now operate with higher friction and lower information quality.

Mercer’s Global Talent Trends 2026 report, surveying 12,000 workers worldwide, found that employee concerns about AI job loss jumped from 28% in 2024 to 40% in 2026. Sixty-two percent feel leaders underestimate AI’s emotional and psychological impact. The anxiety is highest among workers with 5–15 years of experience—the cohort that occupies mid-level roles. They’re skilled enough that their work could theoretically be automated, but experienced enough that the automation would require sophisticated systems that don’t yet exist at production scale. They’re in the worst possible position: too expensive to justify keeping if AI might eventually work, too embedded in complex workflows to be easily replaced today.

The Capital Reallocation Calculus

The binding constraint isn’t technology—it’s capital allocation under uncertainty. Tech companies face a trilemma: they can maintain current headcount and lag in AI investment, they can lay off workers to fund AI infrastructure and hope the technology matures before organizational capacity erodes, or they can attempt to do both by increasing leverage. Most are choosing the second option, which explains why layoffs and AI capex are rising simultaneously.

Oracle’s plan to cut 30,000 workers while expanding data centers reflects this calculus. The company isn’t claiming that agentic AI can replace those workers today. It’s claiming that by the time the data centers are operational—18 to 36 months from now—the AI trained on that infrastructure will have reached sufficient capability. The bet is that you can compress and reconstitute an organization faster than you can build compute clusters. It’s a bet against Conway’s Law, which holds that system architectures mirror the communication structures of the organizations that build them. If you destroy the organization, you destroy the implicit architecture that made the system legible.

The other factor driving this is investor pressure. Markets reward companies that credibly signal they’re positioned for an AI-driven future. Announcing layoffs framed as “AI transformation” provides that signal, even if the AI in question is vaporware. It’s cheaper to lay off mid-level workers now and claim you’re “leaning into agentic automation” than to admit you’re cutting costs because growth has stalled. The political economy of corporate narrative construction incentivizes exactly this kind of strategic ambiguity.

Deutsche Bank analysts warned in January that “anxiety about AI will go from a low hum to a loud roar this year,” noting that many companies attributing layoffs to AI are engaged in “AI redundancy washing”—using the technology as cover for financially motivated cuts. Oxford Economics went further, arguing that macroeconomic data doesn’t support claims of structural AI-driven unemployment. Instead, the firm sees “a cynical corporate strategy: dressing up layoffs as a good news story rather than bad news, such as past over-hiring.”

The Asymmetric Information Problem

Mid-level employees face an asymmetric information problem. They can observe their company announcing AI initiatives and cutting headcount, but they can’t observe whether the AI capabilities being developed will actually replace their functions. The rational response is to start looking for exits, which creates a selection effect: the most talented and mobile workers leave first, while those with fewer options remain. This is the opposite of what companies need if they’re genuinely trying to build AI systems that encode organizational knowledge. You want your best institutional knowledge carriers to stay through the transition so their expertise can be captured. Instead, the transition itself drives them out.

Gen Z workers, ironically, have the highest “AIQ”—AI readiness and capability—at 22%, compared to just 6% for Baby Boomers, according to Forrester. Yet companies are disproportionately eliminating entry-level positions, the roles where Gen Z would typically enter the workforce. Analysis from the Burning Glass Institute shows dramatic declines in entry-level opportunities: a 67% drop in UK graduate job postings since 2022, and 43% in the U.S. Jobs have fallen sharply even in low AI-exposure sectors like HR (77% decline) and civil engineering (55%), suggesting broader economic factors are at play beyond just automation.

The data reveals a perverse outcome: companies are shutting out the cohort most capable of working with AI from the labor market, while simultaneously claiming they need to cut mid-level workers because AI will replace them. The actual logic is simpler and grimmer. Entry-level hiring is expensive and speculative—you’re betting on someone’s future productivity. Mid-level firing is immediately accretive to margins, especially if you can frame it as strategic transformation rather than cost reduction. The AI narrative serves both objectives: it justifies not hiring juniors (the AI will do their work) and it justifies firing mid-level workers (the AI will do their work too).

What the Forrester Rehiring Pattern Reveals

Forrester’s finding that half of AI-attributed layoffs will be quietly rehired, often offshore or at lower salaries, exposes the mechanism. Companies aren’t replacing human labor with AI—they’re using AI as leverage in a negotiation over wages and working conditions. The threat of automation depresses labor’s bargaining power. Workers who might have demanded raises or better conditions now accept stagnant wages to avoid being “automated away.” And when companies realize the AI can’t actually do the work, they rehire, but under worse terms.

This creates a ratchet effect. Each cycle of “AI transformation” weakens labor’s position even if the automation doesn’t materialize. The threat is sufficient to change behavior. Over time, this erodes the economic returns to mid-level expertise. If building institutional knowledge no longer protects you from layoffs—if you can be cut and replaced with cheaper offshore labor once you’ve trained the AI that didn’t actually work—the rational response is to never accumulate firm-specific knowledge in the first place. Stay mobile, stay generic, optimize for skills that transfer across employers. That’s optimal for individual survival but catastrophic for organizational capability.

The companies most aggressive about AI-driven layoffs are the ones most likely to discover, in 2028 or 2029, that they’ve destroyed something irreplaceable. The knowledge embedded in a functioning mid-level layer isn’t just procedural—it’s relational, contextual, tacit. It’s knowing that the CFO gets terse in Q4, that the engineering VP needs decisions framed as technical choices, that the key customer relationship depends on the account manager’s personal rapport built over five years. None of this can be extracted via exit interviews or documented in Confluence pages. And when it’s gone, the organization doesn’t just move slower. It moves blindly, with higher error rates, more misalignments, and an increasing reliance on executive micromanagement to compensate for the missing coordination layer.

The AI displacement story is being told as a technology story. It’s actually a capital allocation story with technology characteristics. The displacement is real, but the mechanism isn’t sophisticated algorithms replacing human judgment. It’s executives making a calculated bet that they can tolerate organizational degradation in exchange for lower labor costs and higher AI infrastructure spend, and that by the time the degradation becomes critical, the AI will have closed the gap. Some will win that bet. Most won’t. And the workers caught in the arbitrage—the mid-level knowledge workers with 5 to 15 years of experience, too expensive to keep and too embedded to easily replace—will bear the cost of the experiment, regardless of whether it succeeds.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Layoff data from Layoffs.fyi, BusinessToday, InformationWeek; executive survey data from Resume.org and Mercer Global Talent Trends 2026; analysis from Harvard Business Review, Forrester Research, Oxford Economics, Deutsche Bank; labor market research from Stanford University, Yale Budget Lab, Burning Glass Institute