Google blanketed the internet with Gemini ads throughout 2025, showcasing AI-generated videos of crocodiles walking across lily pads with pomegranate scales. OpenAI pushed image creation. Anthropic promoted Claude’s reasoning abilities. The pitch was irresistible: creativity democratized, productivity unleashed, the future at your fingertips for twenty dollars a month.

But here’s what the ads didn’t show: a minimum wage worker earning $7.25 an hour—still the federal baseline in twenty-one states—calculating whether that monthly subscription generates enough value to justify the cost. The math is brutal. At forty hours a week, that worker grosses $1,160 before taxes. A $20 AI subscription consumes nearly 2% of pre-tax income for tools that primarily generate… what, exactly? A viral social media post? A whimsical video of impossible creatures? Perhaps an enhanced resume—though even that utility dissolves quickly once the subscription lapses and the polished document sits static in an inbox.

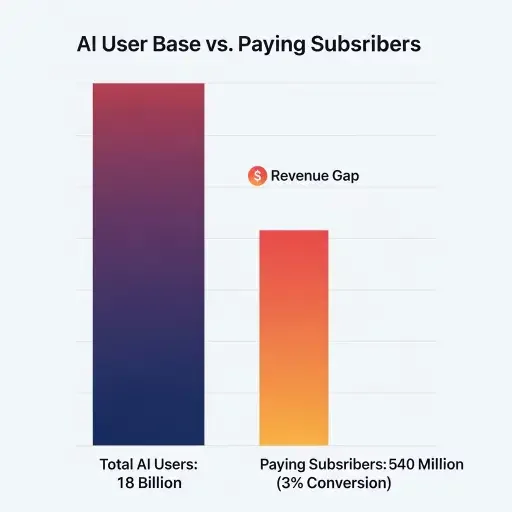

The disconnect between consumer AI’s promise and its economic reality has crystallized into numbers that venture capitalists are now confronting with increasing discomfort. According to Menlo Ventures’ 2025 State of Consumer AI report, approximately 1.8 billion people globally have used AI tools in the past six months. If these users paid an average of $20 monthly for premium services, the market would generate $432 billion annually. The actual consumer AI market? Around $12 billion—meaning only 3% of users convert to paying subscribers. Even ChatGPT, with its commanding first-mover advantage, converts merely 5% of weekly active users into subscribers.

“This is one of the largest and fastest-emerging monetization gaps in recent consumer tech history,” the Menlo report notes with remarkable understatement. For context, Facebook took five years to reach $777 million in ad revenue with 360 million users—about $2 per user annually. Consumer AI reached 1.8 billion users in just 2.5 years but extracts even less revenue per capita than Facebook did in its infancy, and substantially less than Twitter, Google AdWords, or mobile app stores during their comparable growth phases.

The explanation isn’t that consumers don’t value AI—usage data suggests enthusiastic adoption for practical tasks. The problem is that most use cases don’t generate sufficient personal ROI to justify recurring payments. OpenAI’s own research examining 1.5 million ChatGPT conversations found that three-quarters of usage focused on “practical guidance, seeking information, and writing”—mundane productivity tasks that feel valuable in the moment but hard to monetize when free alternatives exist. Creating AI videos of fantasy creatures or generating images for social media likes delivers entertainment value, not economic value. These are tools designed for professional creative studios, not consumers seeking fleeting engagement.

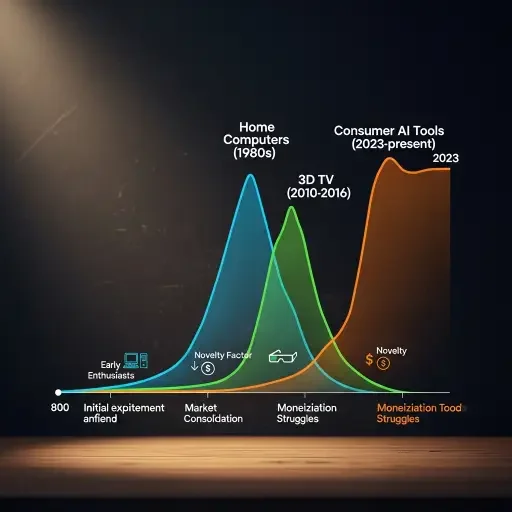

The analogy to 3D TV’s spectacular failure is inescapable. Between 2010 and 2012, manufacturers shipped 41.45 million 3D television units, convinced that Avatar’s theatrical success would translate to living rooms. The technology faced immediate headwinds: expensive glasses ($150 per pair), incompatible formats across brands, limited content, physical discomfort, and—most critically—timing. Americans had just purchased new digital TVs to comply with the 2009 analog-to-digital transition mandate. The additional $500 premium for 3D capability bought a gimmick that solved no actual problem. ESPN 3D shut down in 2012 citing “limited viewer adoption,” and by 2016, even premium manufacturers discontinued their 3D lines entirely. The fundamental error was assuming theatrical novelty would create sustained home demand. It didn’t.

Consumer AI tools risk repeating this pattern. The “wow” factor of generating a video or image is powerful on first encounter but rapidly loses luster. Sora, OpenAI’s video generation standalone app, achieved 12 million downloads but SensorTower estimates day-30 retention below 8%—compared to 30%+ for successful consumer apps. ChatGPT demonstrates better retention (50% at month 12 for desktop users) because it addresses genuine productivity needs. But even ChatGPT’s free tier satisfies most users’ requirements. The premium features—faster responses, priority access during peak times, extended context windows—offer incremental improvements that most consumers simply cannot justify against budget constraints.

The enterprise adoption story tells a radically different tale. Organizations spent $13.8 billion on AI in 2024, a 6x increase from the prior year. In 2025, enterprise AI spending has surged further, with average monthly spend per organization reaching $85,521—up 36% from 2024. CloudZero’s 2025 survey found 88% of enterprise teams now use AI regularly, with 92% reporting improved workflow efficiency. Enterprises can calculate clear ROI: reduced customer service costs, accelerated code development, automated data analysis, enhanced decision-making systems. These aren’t vanity metrics; they’re measurable productivity gains that justify substantial expenditure.

This bifurcation—enterprises enthusiastically paying while consumers overwhelmingly reject subscriptions—raises an uncomfortable question: are tech companies asking consumers to fund infrastructure they cannot personally monetize?

The question grows more pointed when examining the physical costs of AI deployment. U.S. data centers consumed 183 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024, representing over 4% of total national consumption. In 2025, consumption has continued climbing, and by 2030, this figure is projected to surge 133% to 426 TWh. Google’s capital expenditure reached $85 billion in 2024 and has expanded further in 2025, much directed toward AI capacity. Training Google’s Gemini Ultra cost $191 million; OpenAI’s GPT-4 required $78 million in hardware alone.

These infrastructure costs cascade directly to consumers in data center-dense regions. In the PJM electricity market spanning Illinois to North Carolina, data center demand accounted for an estimated $9.3 billion price increase in the 2025-26 capacity market—63% of the total $14.7 billion cost, representing a 500% surge from the prior year. The independent watchdog Monitoring Analytics stated flatly: “Data center load growth is the primary reason for recent and expected capacity market conditions, including total forecast load growth, the tight supply and demand balance, and high prices.”

Residential bills are absorbing these increases. In 2025, Virginia—home to the world’s highest concentration of data centers—saw electricity prices jump 13% year-over-year. Illinois increased 16%. Ohio rose 12%. Maryland residents face projected increases of $18 monthly, while Ohio households anticipate $16 monthly hikes. Bloomberg analysis found that wholesale electricity prices have more than doubled since 2020 in markets near data center clusters, with over 70% of nodes recording price increases located within 50 miles of significant data center activity. A Carnegie Mellon study estimates data centers could drive an 8% average increase in U.S. electricity bills by 2030, potentially exceeding 25% in high-demand markets like northern Virginia.

The Union of Concerned Scientists analyzed costs in seven PJM states and tallied $4.3 billion in 2024 alone for grid connection infrastructure directly serving data centers—costs spread across all ratepayers under existing utility practices. Many of these connections cost $25-100 million each, building transformers and transmission lines on data center properties while distributing expenses to residential customers. These costs have continued accumulating in 2025 as data center expansion accelerates.

So consumers face a pincer movement: subscription costs they cannot justify for services delivering minimal personal ROI, and electricity cost increases subsidizing infrastructure that primarily serves enterprise customers and tech companies’ speculative consumer products.

Tech companies naturally contest this framing. Some argue data centers create economic benefits through jobs and tax revenue. Others note that adding large customers to the grid can spread fixed infrastructure costs across more users, theoretically reducing per-unit prices—though this logic breaks down when infrastructure must be built or upgraded to accommodate the new load. A Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory study examining state-level load growth between 2019-2024 found mixed results, with some cases showing reduced retail electricity prices, though the authors acknowledged uncertainty about whether this trend would persist given the accelerating nationwide demand surges seen in 2025.

But the central tension remains: who captures the value, and who bears the costs? Enterprises demonstrably extract sufficient value from AI to justify aggressive spending. Tech companies are building massive infrastructure on the expectation of future consumer revenue that current conversion rates suggest may never materialize at the required scale. Meanwhile, household electricity bills increase to support data center expansion, and workers earning $7.25-$15 hourly are bombarded with ads for $20 monthly subscriptions to generate content with no clear economic return.

The historical parallel extends beyond 3D TV. Early home computers in the 1980s faced similar adoption challenges. The Commodore 64, Sinclair ZX Spectrum, and BBC Micro sold millions of units because hobbyists loved technology for its own sake—tinkering had intrinsic value. As computers became mainstream consumer products, the value proposition needed to shift from “interesting gadget” to “solves real problems.” Word processing, spreadsheets, and communication tools justified the cost for businesses and home offices. Gaming provided entertainment value that many consumers would pay for. But pure technical capability without clear utility became harder to monetize.

Consumer AI tools occupy an awkward position on this spectrum. They’re genuinely impressive technically—generating coherent images, videos, and text from prompts represents remarkable engineering. But for the average consumer, these capabilities don’t translate into clear, recurring value. The tools feel like solutions searching for problems, or entertainment that loses novelty quickly, rather than productivity enhancements that justify ongoing expenditure in 2025’s economic environment.

The companies building consumer AI face pressure to demonstrate that their massive infrastructure investments will generate returns. OpenAI achieved $10 billion in annualized recurring revenue by mid-2025—impressive, but largely from enterprise and API customers rather than consumer subscriptions. ChatGPT Plus has approximately 12 million paying subscribers at $20 monthly, generating perhaps $2.8 billion annually. For comparison, Meta generates over $130 billion annually from advertising to a comparable user base. The consumer AI monetization model looks anemic by comparison.

Some companies are already retreating from aggressive consumer plays. Business Insider reported that “vibe coding” tools like Lovable saw traffic plunge nearly 40% from summer 2025 peaks, exposing weak retention despite initial hype. Runway ML adopted credit-based pricing where a $12 monthly plan covers only 50 seconds of AI video generation—effectively pricing most consumers out of serious usage. Canva raised Teams pricing by up to 300% in 2024, explicitly citing AI expansion costs, and has continued gating meaningful AI capabilities behind paywalls in 2025.

The shift signals recognition that consumer AI may primarily serve as a loss leader or brand-building exercise while enterprises provide actual revenue. But if that’s the emerging business model, it raises the question more sharply: why should residential electricity customers subsidize infrastructure for services that don’t deliver them commensurate value?

Tech companies might argue they’re not seeking subsidies—they pay for electricity at commercial rates and fund massive capital expenditures. This is technically accurate. But when data center demand drives regional capacity shortages, triggering grid upgrades whose costs spread to all ratepayers under traditional utility regulation, a subsidy emerges regardless of intent. In regions with heavy data center concentration, wholesale electricity prices have surged dramatically over the past five years, and residential rates have increased by double-digits, meaning consumers are bearing costs generated by demand they don’t control and may not benefit from.

The policy implications are beginning to percolate through state legislatures. Oregon passed the POWER Act in 2025, designed to ensure utilities strike fairer cost-sharing arrangements with data centers and crypto miners. Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission projects that while data centers currently cover their own usage, locals could see $14-37 monthly increases as infrastructure demands grow. Senator Elizabeth Warren opened a Senate investigation into whether AI data centers are driving up electricity bills, though the inquiry presumes the conclusion. Senator Bernie Sanders called for a moratorium on data center construction, citing emissions and utility bill impacts.

These political responses remain reactive and unfocused, treating symptoms rather than addressing the fundamental economics. The core issue isn’t data centers per se—computing infrastructure serves legitimate needs. The problem is the mismatch: infrastructure costs socialized across ratepayers, value capture concentrated in enterprises and tech companies, consumer tools that deliver insufficient ROI to sustain the revenue projections justifying the infrastructure build-out.

If consumer AI cannot demonstrate genuine value that users will pay for at scale, the infrastructure supporting it becomes speculative overbuilding—funded partially by capital markets expecting future returns, and partially by electricity customers whose bills rise to power data centers serving applications they don’t use or find insufficiently valuable to subscribe to.

The resolution likely lies in more honest accounting of where value flows. Enterprise AI demonstrates clear ROI and should drive infrastructure investment proportional to enterprise demand. Consumer AI tools that succeed will be those solving real problems—financial management, learning, connection—rather than generating novelty content. The current model of aggressive consumer marketing for tools with unclear personal value propositions, supported by infrastructure whose costs partially shift to households, cannot persist.

Tech companies face a stark choice: develop consumer AI products that deliver genuine value users will pay for, or acknowledge that consumer AI remains primarily an enterprise business where free consumer tiers serve marketing purposes while enterprises provide revenue. Either path is viable. What’s not viable is the current trajectory—massive infrastructure build-out predicated on consumer revenue that conversion rates suggest won’t materialize, while residential electricity customers absorb cost increases to power data centers serving products they cannot economically justify subscribing to.

The AI revolution may be real. But revolutions have a habit of sending the bill to those least positioned to pay it—and least likely to capture the spoils.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Menlo Ventures State of Consumer AI 2025, Bloomberg energy market analysis, Pew Research Center data center study, CloudZero AI cost report, a16z consumer AI rankings