The line is clean enough to slip into a napkin, and that, in itself, is Mencken’s paradox: a sentence so sharp it can cut through the noise and still miss the ground it pretends to cover. “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” The poet of irony could have been mapping not just intellectual mischief, but a market-facing discipline: the human brain loves a clean conclusion when the world delivers a messy surface. The allure of the simple solution is not a failure of intellect; it’s a feature of information processing under pressure. We crave compressions that fit our working-memory budget. Yet, as with any compression, fidelity suffers at the edges.

”

To understand why the temptation persists, we must track three lanes: cognitive economy, signal-to-noise, and the social ecology of decision-making. On the cognitive plane, humans optimize for speed over exhaustiveness. We push for a heuristic that works, then declare victory. In markets and policy alike, speed often becomes virtue, misalignment becomes tragedy, and simple truths act as a public-relations currency. The problem is not that people are lazy; it’s that our mental models are canal systems: they move water efficiently, but they don’t always reach every basin.

Consider the investor who encounters a chart that shows unwavering linear growth and declares, “This is a guaranteed winner.” The simplicity of the line masks path dependencies, regime shifts, and minority risks. The buyer of a tech stock or a policy reform that promises “one clear fix” may discount volatility and feedback loops until a catalyst makes the system snap back into reality. Mencken’s line is not a critique of rationality; it’s a critique of our readiness to mistake narrative for mechanism.

The antidote is not to cultivate perpetual skepticism but to design thinking that distributes perception across layers of abstraction. The first compression layer—the title—acts like a seed that primes a mental model. The second layer—the lede—outlines the macro-architecture: problem, approach, consequence. The micro-architecture within paragraphs uses anchored redundancy and progressive novelty so that the brain is never overwhelmed by a sudden delta of complexity. In practice, this means writing that folds complexity into predictable patterns: given–new, anchor–expansion–conclusion, and repetition that is not repetition but reinforcement with nuance.

In the arena of finance and policy, this is a practical discipline. An “entropically aware” briefing does not present a binary choice between clarity and accuracy; it crafts a narrative around uncertainty itself. It says: here is what we know, here is what we suspect, here is how we test it, and here is how it would look if our assumptions fail. The reader’s brain then travels not along a single axis of truth but along a scaffold that can flex as new data arrives. It is the difference between a single pathway and a branching map—the latter preserves more actionable discriminations under stress.

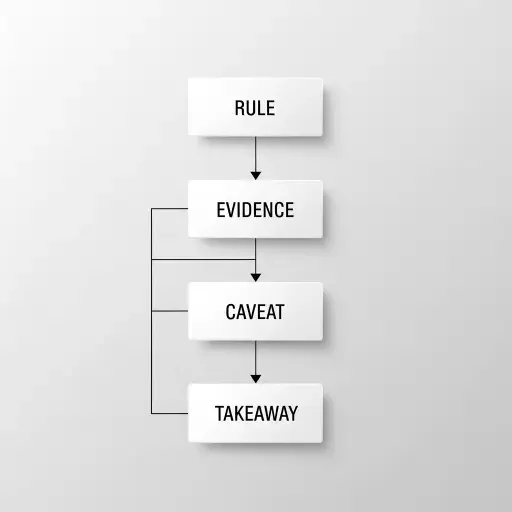

To be concrete, let’s translate Mencken into a decision framework. When confronted with a cascade of data, ask four questions in sequence:

- Is this a problem where a simple rule would capture the essential structure? If yes, proceed with a bounded generalization, but test it against edge cases.

- What is the smallest, most communicable unit of evidence that changes the reader’s model? Present that first, then introduce supporting details.

- Where could a misleading compression occur? Identify the hidden losses—assumptions, regime shifts, covariate changes—and surface them with explicit caveats.

- What is the durable takeaway—the principle that remains useful even if specifics shift? State a single actionable rule anchored in that principle.

This is not cynicism about complexity; it is a design practice for complexity. Businesses, scientists, and public institutions ship decisions under pressure; the goal is to ship reasoning with the same cadence: robust at the core, gracefully adaptable at the edges. Mencken’s warning, reframed as a design guideline, becomes: banish the illusion of the universal truth that survives any test, and embrace a narrative architecture that reveals how truth evolves.

In the end, the most persuasive case for a complex idea is not its finality but its resilience. A proposition that remains legible across methods, datasets, and audiences earns trust not by being the simplest but by being the most structurally honest. The “clear, simple, and wrong” trap is a reminder to carry a second instrument: the epistemic humility to show what a model misses, and the procedural rigor to test what a simple answer neglects.

The price of elegance, in other words, is not ambiguity but sloppy inference. The cure is a prose that distributes meaning across layers, much like a well-structured investment memo that balances clarity with contingency. If you read Mencken and feel the tug toward a single, tidy verdict, resist the pull. Instead, design your thinking to stay ahead of the question: not one answer, but a navigable landscape—mapped, tested, and ready for revision as the data himself changes his mind.

Sources

Quotations from H. L. Mencken; cognitive science on surprisal and structure; organizational decision theory; historical episodes of simplifying failures in finance and policy.