Every shift in legal doctrine collapses a layer of managerial optionality. The latest—courts and administrative agencies increasingly treating telework as a “reasonable accommodation” under disability protections—does that collapse with financial consequences. What was once an HR nicety or pandemic-induced experiment has become, in many jurisdictions, an enforceable baseline. Employers, HR leaders, and investors must translate doctrine into processes or pay in liability, talent loss, and reputational capital.

Why this matters, fast: under anti‑discrimination statutes and administrative guidance, the binding question is not whether telework is convenient but whether it meaningfully enables an employee with a disability to perform essential job functions without imposing undue hardship on the employer. That reframes routine managerial choices—job descriptions, essential functions, attendance policies—into legal vectors. A vague “office-first” policy no longer safely immunizes firms.

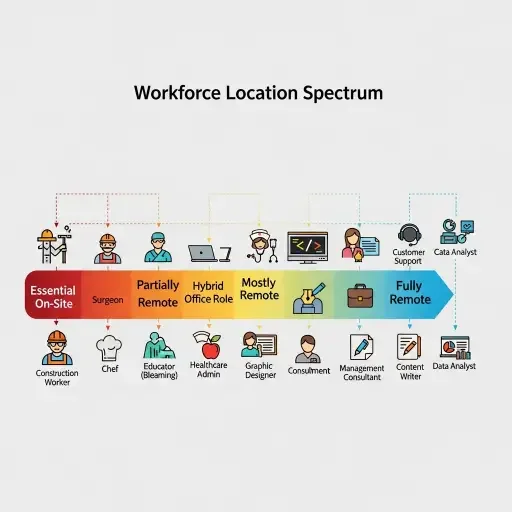

A customer‑support specialist who can perform all core phone‑based duties from home but cannot commute due to a chronic condition requests permanent telework. Courts have increasingly ruled that if the role’s essential functions are remote‑compatible, denying telework can violate disability law absent clear, documented undue hardship. Put bluntly: employers who ignore this risk will face not just EEOC complaints but costly settlements and, importantly, attrition of experienced employees.

Operationally, three pivots matter.

-

Recode “Essential Functions” with discipline. Job descriptions are legal artifacts now. Employers must audit every role to ask: which tasks are truly non‑delegable and location‑bound? Employees and courts will test those claims. The audit should pair task analysis with output metrics (response times, resolution quality) to show equivalence between on‑site and remote task performance.

-

Document interactive processes. The reasonable‑accommodation obligation is interactive. Employers should train managers to engage promptly, record discussions, and explore alternatives (flex schedules, hybrid designs, assistive tech) before issuing denials. A paper trail converts discretionary judgments into defensible decisions; its absence converts them into liability.

-

Reprice “undue hardship” beyond payroll arithmetic. Undue hardship is not merely the cost of a laptop; it is the business disruption reasonably expected from an accommodation. That calculus must be modeled: cybersecurity exposure of remote endpoints, team coordination friction quantified against productivity baselines, and the costs of knowledge transfer if talent departs. Importantly, many of the alleged costs are manageable; turning them into boxes to check reduces legal exposure and improves retention.

These are not only compliance measures; they are value levers. A disciplined accommodation program reduces turnover among experienced staff with disabilities—a cohort that historically faces elevated attrition. It also widens the talent funnel and, when implemented with a view to productivity metrics, can preserve or improve output per dollar. For investors, the takeaway is straightforward: governance that treats accommodation as operational design, not ad hoc charity, reduces regulatory and human‑capital risk.

Yet practical trade‑offs remain. For certain roles—on‑site machinery maintenance, secure facilities work—telework is genuinely infeasible. The hard question is the boundary case: roles that mix synchronous collaboration with discrete deliverables. Here, hybrid job designs and documented trial periods are the pragmatic middle ground: test, measure, document. If performance falters in the hybrid model, the employer has both evidence and options.

Two legal realities shape risk assessment. First, administrative guidance and case law tilt local standards: federal statutes set the architecture, but state and circuit courts—and state anti‑discrimination laws—fill in the details. Employers operating across jurisdictions must calibrate to the strictest relevant standard or accept litigation arbitrage. Second, the presence of a pandemic-era remote baseline complicates “undue hardship” arguments; courts may ask why a business could operate remotely during COVID but claims inability now.

For HR, the checklist is succinct: (a) audit job descriptions; (b) train managers on the interactive process; (c) document every request and the evidence considered; (d) quantify and, where possible, mitigate cybersecurity and coordination risks; (e) run short pilots and measure outputs. Those steps convert legal compliance into governance signals that matter to boards and investors.

Boards should treat telework accommodation as an emerging governance metric. Disclosure around workforce policies—how requests are handled, denial rates, and measurable outcomes—belongs in risk registers. For PE or public investors, a pattern of denials with weak documentation is a litigation and reputational vector; a robust accommodation program is a mitigant that preserves human capital and limits headline risk.

The core operational principle: treat accommodation as design, not charity. Reframing telework as an engineering problem—define functions, instrument performance, iterate—converts liability into capability. That conversion is where compliance and shareholder value quietly align: fewer lawsuits, less churn, and a broader, more resilient talent base.

The legal landscape has shifted. Employers who make the minimal moves—rewriting job definitions, instituting documented interactive processes, and modeling undue‑hardship claims—will reduce risk and retain talent. Those who don’t will find the cost of posture suddenly larger than the cost of adaptation.

Tags

Related Articles

Sources

Federal court decisions and EEOC guidance on telework accommodations; ADA compliance documentation; HR industry research and legal analysis; employment law journals and workplace policy studies.