The Nine-Year Promise

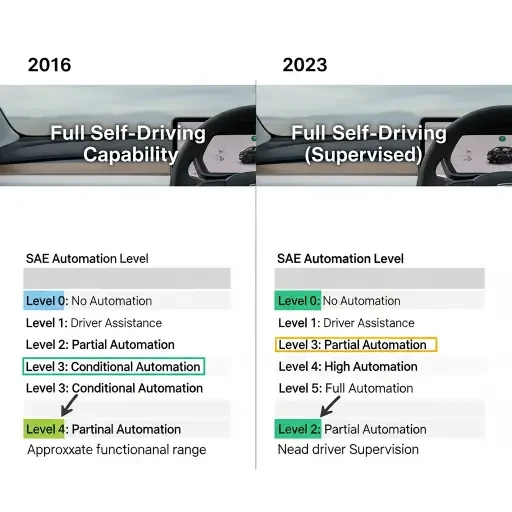

Since 2016, Tesla has sold a software package called Full Self-Driving. The name suggests autonomy—a car that navigates without human intervention. The reality: SAE Level 2 driver assistance, requiring continuous human supervision, hands on wheel, eyes on road. In automotive engineering taxonomy, Level 2 sits four levels below true autonomy. The gap between the name and the capability became California's legal argument.

The California DMV initiated its investigation in 2021, formally accusing Tesla of false advertising in 2022. The agency's position: branding like "Autopilot" and "Full Self-Driving" created expectations of autonomy that Tesla's technology couldn't deliver. Tesla's defense argued the company had been using these terms for years without regulatory pushback, suggesting implicit permission to continue. The court found this argument unpersuasive.

The case crystallized around what regulators call "net impression"—the overall message consumers receive from marketing, regardless of disclaimers. When headlines promise self-driving and fine print requires supervision, which message wins? California's answer arrived Tuesday: the headline always wins, and that makes it deceptive.

The Compliance Window

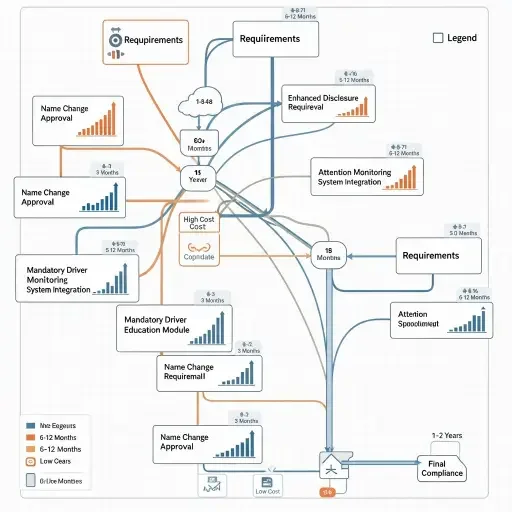

The DMV adopted the judge's ruling with modified penalties: Tesla has 60 days to fix deceptive marketing claims, after which a 30-day sales suspension takes effect. Crucially, the DMV stayed the manufacturing license suspension—Tesla's Fremont factory won't shut down. But sales in California, which represents roughly one-third of Tesla's U.S. deliveries, would halt for a month if compliance fails.

Steve Gordon, the DMV director, emphasized the agency's intent to be fair while maintaining consumer protection standards. The message: fix the marketing language, avoid the suspension. What constitutes "fixed" remains deliberately vague. The DMV hasn't published specific compliance standards, only referenced Federal Trade Commission guidelines for "clear and conspicuous" disclosures—meaning disclaimers must be as prominent as claims.

Tesla has several remediation pathways. The most straightforward: retire "Full Self-Driving" as a product name, replacing it with terminology that accurately reflects SAE Level 2 capabilities—perhaps "Advanced Driver Assistance" or "Supervised Driving Features." The company already added "(Supervised)" to the name in recent years, acknowledging the need for active driver monitoring. Whether that addition satisfies regulators depends on whether it sufficiently counterbalances the "Full Self-Driving" portion of the brand.

Alternative approaches include restructuring all marketing materials to ensure disclaimers appear with equal prominence to capability claims, implementing mandatory driver education flows before FSD activation, and enhancing in-car monitoring systems to enforce attention requirements. The challenge: Tesla's marketing historically relied on aspirational messaging—cars with "all hardware needed for full self-driving"—which regulators now view as fundamentally misleading.

The Pattern of Promises

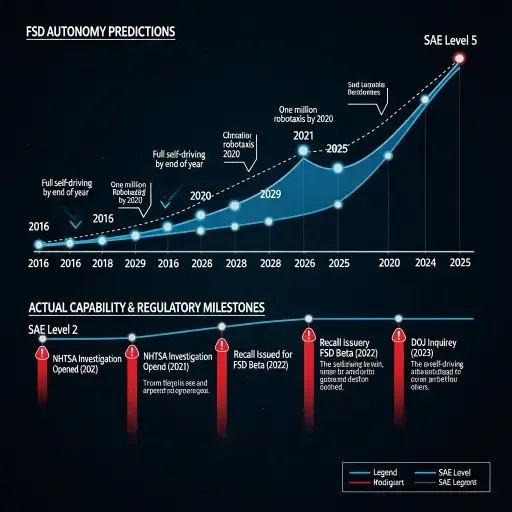

Tesla has sold Level 2 driver assistance software since 2016 under the Full Self-Driving name, despite the software never making cars capable of driving themselves. The timeline of unfulfilled predictions compounds the deception claim. In 2016, Elon Musk announced all Tesla vehicles included hardware for full autonomy, predicting coast-to-coast autonomous demonstrations by 2017. In 2018, he promised feature-complete self-driving by 2019. In 2020, he claimed it would arrive by year-end. Each deadline passed without delivery.

These weren't private projections—they were public marketing claims made on earnings calls, at press events, and across social media. They influenced purchasing decisions. Customers paid $5,000 to $15,000 for FSD packages based on representations that full autonomy was imminent, contingent only on software updates. Years later, those vehicles remain Level 2 systems requiring constant supervision.

The disconnect between promise and delivery created what California characterizes as ongoing consumer harm. Drivers who purchased FSD in 2016 expecting near-term autonomy received software updates, but never the fundamental capability shift from assistance to autonomy. This forms the basis of multiple class action lawsuits now proceeding through federal courts, with certified classes covering California residents who purchased FSD between 2016 and 2024.

The California legislature passed a law specifically banning automakers from deceiving consumers about autonomous capabilities, giving the DMV additional enforcement authority. The timing wasn't coincidental—it arrived during Tesla's administrative proceedings, signaling legislative support for the DMV's position.

The Safety Arithmetic

Federal safety regulators have documented persistent concerns. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration currently investigates FSD following reports of over 50 incidents involving red-light violations and improper lane usage. Another probe examines crashes occurring in low-visibility conditions. These investigations reflect pattern recognition—not isolated incidents but systematic behavior suggesting the technology operates outside safe parameters under certain conditions.

Musk himself previously acknowledged that Autopilot sometimes creates overconfidence among drivers, and regulators have documented more than a dozen fatal crashes with Autopilot engaged. This admission cuts against Tesla's defense. If the company's CEO recognizes that the technology's naming and capabilities create dangerous driver complacency, arguing those same names don't mislead consumers becomes untenable.

The safety implications extend beyond individual crashes. When marketing creates false confidence in automation capabilities, drivers disengage from the driving task prematurely. They check phones, watch videos, or simply stop paying attention—behaviors that Level 2 systems cannot safely accommodate. The technology requires paradoxical human engagement: constant vigilance while the car handles routine driving. Marketing that emphasizes "self-driving" undermines the vigilance requirement.

NHTSA's regulatory approach to advanced driver assistance systems reflects this tension. The agency lacks specific performance standards for Level 2 systems, relying instead on post-market surveillance and recalls when problems emerge. Tesla has faced multiple recall actions—most recently expanding Autopilot recalls to address inadequate driver monitoring. The recalls add software warnings and attention checks, attempting to compensate for the behavioral risks created by marketing messaging.

The Market Structure Problem

California represents Tesla's largest single-state market. The Fremont factory still builds around 500,000 vehicles annually and employs approximately 20,000 people. A 30-day sales suspension wouldn't halt production but would create inventory buildup, logistical complexity, and financial impact concentrated in a crucial quarter. Fourth-quarter deliveries typically represent Tesla's strongest performance; a California ban during this period would materially affect annual results.

Tesla's stock closed at a record on Tuesday, driven by enthusiasm surrounding Robotaxi plans and driverless technology. The market appears to be pricing in autonomy success despite regulatory setbacks—a dynamic that creates interesting reflexivity. If investors believe Tesla will achieve full autonomy soon, the company's valuation remains elevated despite current legal challenges. If legal challenges delay or prevent autonomy deployment, the valuation faces compression risk.

The DMV's enforcement action occurs against this backdrop of elevated expectations. Tesla launched a commercial Robotaxi service in Austin in June 2025, operating with safety drivers in passenger seats. The company promises driverless operation soon. California's regulatory position—that Tesla systematically misrepresents its technology's capabilities—creates direct tension with the Robotaxi narrative. How can regulators trust claims about imminent Level 4 autonomy from a company found to have deceived consumers about Level 2 systems for years?

This credibility deficit extends beyond California. Multiple jurisdictions now scrutinize Tesla's FSD marketing. Germany required marketing changes in 2020. Australia faces class action litigation over similar claims. The pattern suggests regulatory convergence: global authorities increasingly reject aspirational branding for driver assistance technology.

The First Amendment Defense

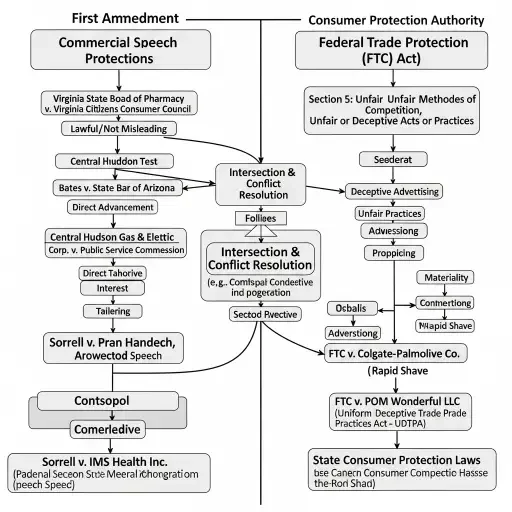

Tesla argued its statements constituted protected speech under the First Amendment, but the judge ruled the company's advertising fell into the category of deceptive commercial claims subject to consumer protection standards. This distinction matters. Political speech, artistic expression, and personal opinion receive broad First Amendment protection. Commercial speech—advertising and marketing—receives narrower protection, balanced against government interest in preventing consumer deception.

The legal standard for commercial speech regulation requires that claims be verifiable and not misleading. Tesla's statements about hardware capabilities and autonomy timelines meet the verifiable threshold—they make specific factual claims about vehicle capabilities and future performance. The question becomes whether those claims mislead consumers about what they're purchasing.

California's position: calling Level 2 technology "Full Self-Driving" inherently misleads, regardless of disclaimers. The name itself creates a false impression that overwhelms qualifying language. This framing shifts burden from proving individual consumer harm to demonstrating systematic misrepresentation through marketing design.

The court's acceptance of this argument establishes important precedent. It suggests automotive regulators can restrict product naming based on misleading impressions, even absent specific false statements. "Full Self-Driving" becomes problematic not because Tesla explicitly claims vehicles drive themselves—the company always included supervision requirements in fine print—but because the name implies capabilities the technology lacks.

The Remediation Challenge

The DMV has not offered a public standard or definition for compliance, requiring Tesla to interpret what constitutes adequate remediation. This creates implementation risk. Tesla could make good-faith changes that regulators deem insufficient, exhausting the 60-day window without achieving compliance. The lack of clear standards makes strategic planning difficult.

One benchmark: Federal Trade Commission guidelines for clear and conspicuous disclosures require disclaimers to be as prominent as claims. Applied to Tesla, this would mean every instance of "Full Self-Driving" must be accompanied by equally visible text stating "Requires Active Driver Supervision" or similar language. Website headers, in-car displays, purchase agreements—all would need restructured to ensure supervision requirements receive equal prominence.

A more aggressive interpretation might require eliminating "Full Self-Driving" entirely from marketing vocabulary. The phrase itself could be deemed inherently misleading regardless of accompanying disclaimers, similar to how "fat-free" must accurately describe nutritional content, not aspirational health outcomes. Under this standard, Tesla would need complete rebranding—perhaps "Tesla Advanced Driver Assistance" or "Tesla Supervised Driving."

The company has already made naming adjustments, adding "(Supervised)" to the FSD brand. Whether this modification satisfies regulators remains unclear. The addition acknowledges supervision requirements but doesn't eliminate the core "Full Self-Driving" claim that creates misleading impressions. It's possible California views the current naming as progress but insufficient for full compliance.

Implementation complexity extends beyond naming. Tesla's entire marketing architecture—from website design to social media messaging to CEO communications—would require coordination. Elon Musk's X posts about FSD capabilities constitute marketing under California's interpretation, given Tesla lacks a traditional PR department and relies on Musk's personal communications for product promotion. Ensuring consistent, compliant messaging across all channels within 60 days presents significant operational challenge.

The Recursive Question

Tesla's response to the DMV's 2022 inquiry essentially argued it had been allowed to use misleading terminology for so long that it should be permitted to continue. This defense reveals core tension: at what point does widespread practice become established meaning? If millions of consumers understand "Full Self-Driving" to mean "advanced driver assistance requiring supervision," has the term's meaning evolved to match reality rather than literal interpretation?

The court rejected this argument, but the question persists. Language evolves through use. "Smartphone" doesn't describe phone capabilities—it describes computing capabilities in phone form factor. "Bluetooth" refers to a medieval king, not wireless protocol characteristics. Brand names often diverge from literal meanings without triggering regulatory action. Why does "Full Self-Driving" merit different treatment?

California's answer centers on safety. When misleading product names create behavioral risks—drivers disengaging from vehicle control based on false autonomy expectations—consumer protection interest overrides linguistic flexibility. The stakes differ from mislabeling consumer electronics or overstating software capabilities. Automotive marketing that induces dangerous driving behavior crosses from commercial puffery into actionable deception.

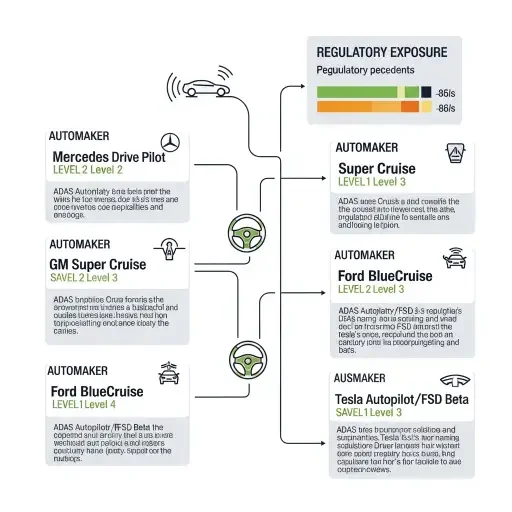

This precedent could reshape automotive industry marketing broadly. Multiple manufacturers deploy advanced driver assistance systems with varying capability claims. Mercedes-Benz offers "Drive Pilot," GM markets "Super Cruise," Ford sells "BlueCruise." Each name suggests autonomy while delivering Level 2 or limited Level 3 functionality. If California's interpretation holds, expect naming scrutiny across the industry. The Tesla ruling becomes template for evaluating whether marketing creates misleading "net impressions" about automation capabilities.

The Sixty-Day Clock

Tesla has until mid-February 2026 to demonstrate compliance. The company hasn't publicly commented on remediation strategy—it dissolved its public relations department years ago, leaving external communications primarily to Musk's social media. This communication structure itself presents compliance challenge: how does Tesla ensure consistent messaging when its primary spokesperson operates independently on platforms outside company control?

Several scenarios seem plausible. Tesla could attempt minimal compliance—enhanced disclaimers, mandatory driver education before FSD activation, more aggressive attention monitoring—while maintaining the Full Self-Driving name. This approach bets regulators will accept incremental improvements without requiring complete rebranding. Risk: the DMV rejects halfway measures and proceeds with suspension.

Alternatively, Tesla might fully rebrand, retiring FSD nomenclature in favor of terminology explicitly signaling Level 2 limitations. This approach guarantees compliance but carries market risk. The FSD brand has substantial value; abandoning it might affect customer perception and purchase intent. Owners who paid thousands for "Full Self-Driving" might resist software that's renamed "Advanced Driver Assistance."

A third path: Tesla challenges the ruling, arguing First Amendment protections or requesting preliminary injunction against sales suspension while appeals proceed. This extends the timeline but maintains current branding during litigation. The strategy carries reputation risk—positioning Tesla as resistant to consumer protection rather than committed to transparency.

The most likely outcome: negotiated compliance. Tesla proposes specific marketing changes, the DMV provides feedback, the parties iterate until reaching acceptable standards. The 60-day window becomes dialogue period rather than unilateral deadline. Both sides have incentives to avoid suspension: California protects consumers without disrupting a major employer; Tesla maintains market access without admitting systematic deception.

Whatever path emerges, the ruling marks inflection point. For nearly a decade, Tesla operated with aspirational branding that regulators tolerated despite evident gaps between names and capabilities. That tolerance has ended. The question shifts from whether Tesla must change to how comprehensively change must occur. The answer arrives by mid-February. And every automotive manufacturer marketing driver assistance technology is watching.

Sources

California DMV proceedings, court documents, Electrek reporting, CNBC coverage, federal class action filings, NHTSA investigation records