The Delaware Court of Chancery occupies a peculiar position in American law—a 233-year-old institution that effectively writes the operating rules for corporate America. Most of the nation's Fortune 500 companies are incorporated in Delaware, which means when billion-dollar acquisitions collapse, when CEOs demand unprecedented compensation packages, when shareholders revolt, they end up in this court. Vice chancellors dissect merger agreements, parse fiduciary duties, and adjudicate the financial architecture of capitalism itself.

And then there's Tucker. A five-year-old goldendoodle with separation anxiety, a fondness for Delaware beaches, and the dubious distinction of being the subject of a novel partition ruling that occupied the same court that recently dismantled Elon Musk's $56 billion pay package. The case is Callahan v. Nelson, and it represents something more unsettling than a simple custody dispute—it's a collision between legal categories designed centuries ago and the emotional reality of how Americans actually live with animals.

The Architecture of the Problem

Karen Callahan and Joseph Nelson were childhood neighbors who reconnected in 2018 and began dating. They acquired Tucker in 2020—the mechanics of acquisition became disputed later, with Nelson's daughter claiming Tucker was intended as a gift for her father, while Callahan testified she paid the veterinary bills and picked up the dog. When the couple separated in 2022, Tucker remained with Nelson. Callahan hasn't seen the dog since.

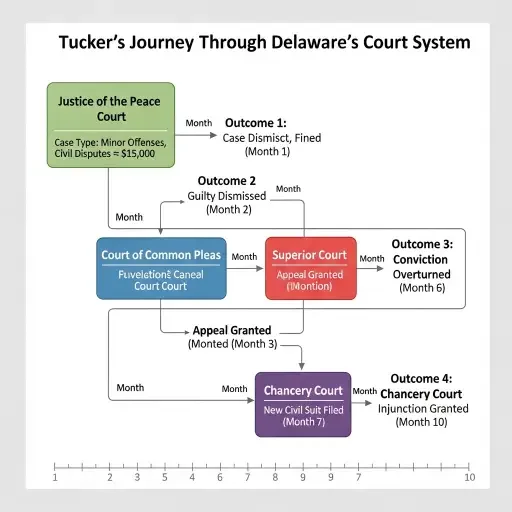

What followed demonstrates how American law transforms personal grief into procedural odyssey. Callahan filed in Justice of the Peace Court, which ruled in her favor. Nelson appealed to Court of Common Pleas, which held a two-day trial and determined Tucker was jointly owned. Callahan appealed to Superior Court, which affirmed joint ownership. Three courts, three different procedural levels, no resolution. The question of who owned Tucker had been answered—both parties did, jointly—but that answer solved nothing about who actually got to keep him.

Delaware law for partitioning co-owned property was written for land and real estate, not living creatures. The statute contemplates physical division of property or, if that proves impractical, a public auction. Vice Chancellor Bonnie W. David acknowledged Tucker doesn't fit easily under Delaware's real property partition statute, which creates an immediate conceptual problem: how do you partition a sentient being without invoking Solomon's blade?

The case landed in Chancery Court because Delaware law recognizes partition as the remedy for co-owners seeking to sever their interests in jointly owned property. It's an equity doctrine, centuries old, designed to prevent one co-owner from holding another hostage through mere possession. For farmland or commercial real estate, the mechanism works elegantly. For Tucker, it required inventing new legal architecture in real time.

Property Law's Category Crisis

Begin with the uncomfortable foundation: the law recognizes dogs as property, even if many of us do not consider them so. This classification traces back over a century, most explicitly to an 1897 Supreme Court ruling establishing citizen-owned dogs as personal property. The categorization made sense in an agricultural economy where dogs functioned primarily as working animals—herders, hunters, guards. Property status provided legal clarity for transactions, disputes, and responsibilities.

But property law assumes fungibility—the principle that one item of a category can substitute for another of equal value. A dollar bill is fungible. A Toyota Camry of specific year and condition is functionally fungible with another identical model. Tucker is not fungible. There exists no market mechanism to establish his "fair market value" beyond what his specific co-owners attach to him, which is precisely what makes partition-by-public-auction absurd.

David called dogs "living, sentient beings with value that transcends economics", acknowledging the category crisis directly. Yet she couldn't simply discard property law's framework—doing so would exceed her judicial authority and create uncertainty about the legal status of millions of pets. The challenge was finding a procedure within existing property doctrine that acknowledged Tucker's non-fungible nature without requiring legislative intervention.

What makes Delaware's predicament particularly acute is timing. Had Callahan and Nelson married, Delaware's Family Court could have determined Tucker's ownership under a 2023 law that enhanced protections for companion animals. That statute directs Family Court to consider the wellbeing of pets in divorce proceedings—acknowledging implicitly that animals occupy a different status than furniture or vehicles. But Callahan and Nelson never married, which meant their breakup fell outside Family Court's jurisdiction entirely.

This jurisdictional gap reveals how American law fragments depending on relationship formality. Marriage creates legal infrastructure—community property rules, divorce procedures, custody frameworks—that non-marital partnerships lack. When married couples split, their dog might get "best interest" analysis. When unmarried co-owners separate, the dog reverts to pure property, subject to partition statutes written for real estate.

The Best Interest Mirage

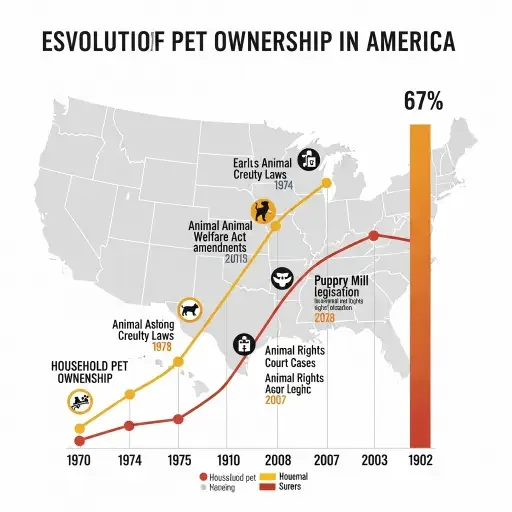

Nelson proposed that the court should consider Tucker's best interests, similar to child custody proceedings. The suggestion has intuitive appeal—if we're acknowledging Tucker is more than furniture, shouldn't we evaluate what's actually better for him? Several states have moved this direction: Alaska became the first in 2017 to require judges to consider pets' wellbeing in divorce, followed by Illinois, California, and New York. These statutes represent legislative recognition that property doctrine doesn't adequately capture how companion animals function in households.

But David rejected the best-interest approach, and her reasoning exposes uncomfortable truths about judicial capacity. While a few courts have applied a best-interests standard when resolving ownership disputes over companion animals, none have explained why that approach should prevail over the common law default of a value-maximizing auction. The judge wasn't being callous—she was identifying a doctrinal vacuum.

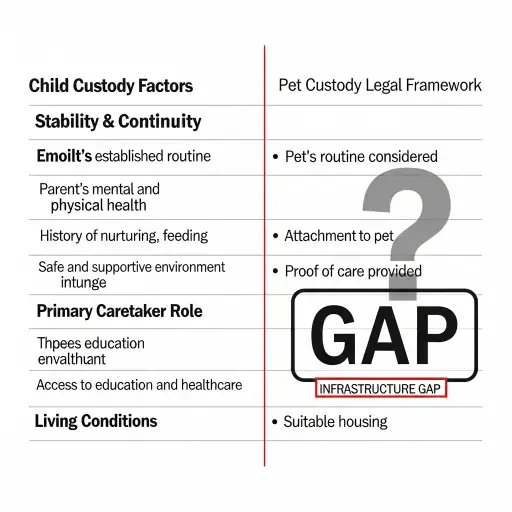

Child custody law developed extensive frameworks for evaluating "best interest"—factors like emotional bonds, stability of living situation, ability to provide care, relationships with other family members. Courts can order home studies, psychological evaluations, expert testimony. The infrastructure exists because legislatures built it, recognizing children deserve more than property-division mechanisms.

For pets, that infrastructure mostly doesn't exist. A veterinary behaviorist testified about Tucker's attachment patterns and separation anxiety—useful information, certainly, but applied within a property partition framework, not a custody determination. David wrote she was "utterly convinced that both parties love this dog and would care for him", which means the best-interest analysis produced no clear winner. When both parties are suitable caretakers and the animal would reasonably adapt to either household, best-interest doctrine provides no decisive guidance.

The deeper problem involves judicial role. Child custody courts expect to manage ongoing arrangements—modifying visitation schedules, adjusting child support, responding to changed circumstances. Family law contemplates continuous judicial oversight because children's needs evolve. Could Delaware's Chancery Court—already managing Fortune 500 litigation, billion-dollar merger disputes, complex corporate governance—really absorb ongoing pet custody management? The answer was implicit in David's ruling: absolutely not.

The Auction Solution and Its Discontents

Faced with partition law's physical division default (impossible for Tucker) and best-interest analysis's doctrinal ambiguity, David ordered a private auction. Callahan and Nelson would bid against each other, highest bid wins Tucker, losing bidder receives cash compensation. An attorney would serve as partition trustee to conduct the auction, ensuring procedural fairness.

The mechanism has brutal elegance. It avoids the impossibility of physical partition. It sidesteps best-interest analysis's evidentiary demands. It acknowledges that Callahan and Nelson value Tucker far more than any public market would, making private auction more appropriate than public sale. And critically, it produces finality—one transaction, one winner, case closed. No ongoing visitation disputes, no modification petitions, no continued court involvement.

But the solution exposes how property law bends reality to fit legal categories. Tucker becomes subject to an auction not because anyone believes auctioning dogs makes moral sense, but because partition doctrine offers limited alternatives and courts prioritize finality over ongoing management. The losing bidder gets cash, which property law treats as equivalent to the thing being partitioned—yet everyone involved understands money cannot replace Tucker for whoever loses.

The auction mechanism also creates perverse dynamics. Whoever has deeper financial resources can simply outbid the other, regardless of emotional bond, caregiving history, or Tucker's actual attachment patterns. If Nelson earns significantly more than Callahan, he wins by default. The procedure measures willingness to pay, treating it as proxy for value—a classic property law move that works fine for land or commodities but feels grotesque applied to a living creature both parties consider family.

What Chancery Court Revealed About Legal Evolution

The Tucker case matters beyond its immediate parties because it exposes how legal categories lag social change. Delaware's Chancery Court didn't create this problem—the court inherited centuries of property doctrine that made sense when dogs were primarily working animals, when fewer Americans lived in cities, when pets occupied different household roles. The institution's prestige made the disjunction visible: if even America's most sophisticated business court struggles to handle pet custody, the problem isn't judicial competence but statutory inadequacy.

The court's chief judge previously had to balance public health risks with a horse owner's demand to retrieve his Clydesdale's remains from a landfill, demonstrating that Tucker wasn't Chancery's first encounter with animals exceeding property law's conceptual boundaries. These cases arrive because Delaware's court system, like most American jurisdictions, lacks specialized forums for disputes involving companion animals. Family courts handle married couples' divorces, civil courts handle property disputes, but unmarried co-owners with jointly owned pets fall through the cracks.

Seven states now have statutes directing courts to consider pets' wellbeing in divorce—Alaska, California, Illinois, New York, Maine, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island. These laws acknowledge, however tentatively, that companion animals occupy a liminal legal status: property by classification, but property that courts should treat differently from furniture. The statutes represent legislative recognition that judicial discretion alone cannot bridge the gap between 19th-century property doctrine and 21st-century household reality.

Yet even these progressive statutes stop short of full best-interest standards. They typically empower rather than require judges to consider animal wellbeing, leaving substantial discretion. They rarely provide the evidentiary frameworks or expert evaluation procedures that child custody law takes for granted. And critically, most apply only to divorce—leaving unmarried couples like Callahan and Nelson outside their protection, as though legal marriage were the only relationship structure deserving animal welfare consideration.

The Broader Implications: When Law Can't Keep Pace

Tucker's journey through Delaware courts illustrates a fundamental challenge for legal systems: how to update centuries-old doctrine when social practices evolve faster than legislatures can respond. Property law's categories—real property, personal property, tangible versus intangible—developed when the distinction between animate and inanimate property seemed clear. Working dogs, livestock, and pets existed, but they occupied different cultural and economic roles. The contemporary American relationship with companion animals—where 67% of households own pets, where animals function as family members, where people spend billions on veterinary care—doesn't map onto historical categories.

The problem compounds because updating legal categories requires political consensus that's difficult to achieve. Animal rights advocates push for personhood status or at minimum "living property" designations that force consideration of animal wellbeing. Agricultural and research interests resist changes that might complicate livestock management or laboratory procedures. Pet industry stakeholders have mixed incentives. Meanwhile, courts confronting cases like Tucker's must work within existing doctrine, unable to simply declare new legal categories into existence.

David's opinion demonstrates judicial candor about these limits. She quoted Kipling's "The Power of the Dog" not as decoration but as acknowledgment that law operates in emotional terrain it wasn't designed to navigate. She cited Solomon not to suggest cutting Tucker in half but to emphasize how ancient the problem of dividing the indivisible actually is. And she ordered an auction not because it's ideal but because existing legal infrastructure offers no clearly better alternative within her authority to implement.

The case also reveals tensions within Delaware's own legal framework. The 2023 Family Court statute protecting companion animals in divorce suggests legislative recognition that pets deserve special consideration—yet that protection evaporates if the couple never married. This creates odd incentive structures: marry briefly and your dog gets best-interest analysis in divorce; cohabit for years and your dog faces partition-by-auction. The law treats relationship formality as dispositive, ignoring that emotional bonds and caregiving responsibilities might be identical.

The Human Cost of Legal Categories

Behind the procedural history and doctrinal analysis lies straightforward human suffering. Callahan hasn't seen Tucker since the 2022 breakup—over three years of separation from an animal she considers family. Nelson faces the prospect of losing Tucker despite three years of daily care and the dog's evident attachment. Tucker himself, regardless of which owner prevails, experienced household disruption and will potentially face another major transition.

The litigation costs alone likely exceed Tucker's monetary "value" by orders of magnitude. Justice of the Peace Court, Court of Common Pleas, Superior Court, Chancery Court—each level requires filing fees, attorney time, expert witnesses. The veterinary behaviorist who testified about Tucker's attachment patterns doesn't come cheap. The partition trustee conducting the auction will charge fees. By the time the process concludes, both parties will have spent thousands of dollars establishing what everyone already knew: they both love the dog.

This resource expenditure reveals another dimension of how property law fails pets. If Tucker were truly equivalent to furniture, the parties would likely accept a lower court's decision rather than pursue multiple appeals. The persistence of litigation demonstrates how inadequately property frameworks capture the stakes involved. Yet because legal doctrine treats Tucker as property, the dispute must proceed through property division mechanisms regardless of their obvious inadequacy.

The case also highlights the absence of alternative dispute resolution infrastructure. Years of litigation have failed to resolve this Delaware dog fight, suggesting that adversarial legal proceedings may be particularly ill-suited for pet custody disputes. Mediation exists as an option, but lacks the legal framework that custody mediation for children provides—no standards, no guidelines, no enforceability mechanisms if agreements break down. The parties are left choosing between inadequate court procedures and informal negotiations with no legal backing.

Delaware's Accidental Test Case

Delaware's prominence in corporate law makes the Tucker case particularly significant. When the Chancery Court confronts an issue, legal observers nationwide pay attention. The court's opinions get cited, analyzed, taught in law schools. Its judges are considered among America's most sophisticated jurists. If this court finds pet partition doctrinally challenging, it signals that the problem isn't local or idiosyncratic—it's structural.

The opinion will likely influence how other courts approach similar cases, even absent Delaware precedent's formal authority outside the state. Judges facing pet disputes in their own jurisdictions will read David's analysis, see how she balanced competing considerations, observe that even Delaware's elite business court found no perfect solution within existing property law. The case functions as a national test of whether current legal categories can accommodate modern pet ownership practices.

But the case also reveals Delaware's limitations. As a corporate law powerhouse, the state has invested heavily in business court infrastructure—specialized judges, expedited procedures, sophisticated doctrine. Family law and property disputes involving ordinary residents receive less systematic attention. The 2023 companion animal statute for Family Court suggests legislative awareness of pets' special status, but that protection doesn't extend to Chancery's property partition jurisdiction. Delaware's legal system excels at corporate governance but struggles with Tucker, revealing how specialization creates blind spots.

What Tucker Predicts About Legal Change

The trajectory of pet custody law likely mirrors earlier evolution in family law itself. Divorce once treated wives as property, children as chattel, household dissolution as purely economic. Decades of social change and legislative reform gradually built the complex family law infrastructure that now governs custody, support, and property division with attention to human wellbeing beyond pure economics. Pet law appears to be in early stages of similar evolution—property classification cracking under the pressure of how people actually relate to animals.

The pattern suggests several likely developments. More states will adopt companion animal wellbeing statutes, though these will probably remain limited to divorce contexts initially. Courts will increasingly struggle with cases like Tucker's, creating pressure for legislative solutions. Eventually, some jurisdiction will attempt more comprehensive pet custody frameworks—perhaps borrowing from child custody law's procedural infrastructure while acknowledging pets aren't children and deserve different analysis.

But the evolution will be slow and uneven, because updating legal categories requires overcoming substantial inertia. Attorneys trained in property law must learn new frameworks. Courts must develop evidentiary standards for evaluating animal wellbeing. Legislatures must navigate competing interest groups. And throughout, millions of pets will continue existing in the liminal space between property and family, their legal status perpetually lagging their household reality.

Tucker's case also predicts increasing strain on court systems ill-equipped for these disputes. As pet ownership rates remain high and American household structures diversify beyond traditional marriage, cases involving unmarried co-owners and companion animals will multiply. Courts designed for either corporate disputes or traditional family law will confront growing caseloads that fit neither category cleanly. Either legislatures create new frameworks or courts will repeatedly improvise, case by case, with inconsistent results.

The private auction solution might become a template—not because it's ideal, but because it offers finality within existing property doctrine. Other courts facing similar situations may cite Delaware's precedent, reasoning that if the nation's preeminent business court found auction acceptable, it must be reasonable. This would represent evolution-by-precedent rather than legislative reform: judges incrementally developing pet partition procedures through common law development, building doctrine from the ground up because statutory frameworks remain inadequate.

The Uncomfortable Equilibrium

David acknowledged the auction process would inevitably result in disappointment, possibly heartbreak, for one of the parties. This candor matters—the court isn't pretending the solution is ideal, merely that it's the best available option within existing legal constraints. The honesty extends to the ruling's core tension: everyone involved knows Tucker isn't furniture, yet law provides only furniture-designed tools to resolve the dispute.

This equilibrium—social reality pulling one direction, legal doctrine constraining another—characterizes Tucker's case but also illuminates broader dynamics of legal change. Law cannot instantly accommodate every shift in social practice. Courts operate within statutory boundaries and doctrinal traditions they cannot simply discard. Legislatures move slowly, requiring political consensus that's difficult to achieve. During the gap between social change and legal adaptation, judges improvise within inherited frameworks, producing decisions that satisfy neither pure property logic nor full recognition of animals' special status.

The Tucker case will resolve—eventually, after the auction, one party will own the dog and the other will receive cash compensation. But the underlying tension won't resolve, because it reflects a fundamental category mismatch between how Americans relate to pets and how law classifies them. That tension will produce more cases like Tucker's, in Delaware and elsewhere, until either legislatures build comprehensive pet custody frameworks or social practices shift to acknowledge the gap between emotional and legal reality.

Perhaps the most telling detail: David included Tucker's photograph in the court opinion, showing him on a Delaware beach. Courts don't typically attach pictures of disputed furniture or real estate to partition rulings. The photograph acknowledges what everyone knows—Tucker isn't property in any meaningful sense that the word conveys. Yet he must be treated as property because legal categories, once established, don't vanish simply because they've become inadequate. And so America's most sophisticated business court ordered an auction for a goldendoodle, producing a ruling that's simultaneously reasonable within existing law and absurd given the actual subject matter.

Tucker remains with Nelson for now, awaiting the auction that will determine his future. Somewhere in Delaware, a very good boy with separation anxiety has no idea that he's become a test case for whether American property law can accommodate the reality of modern pet ownership. The answer, as David's opinion makes clear, is that it cannot—at least not yet, not fully, not without legislative intervention that remains uncertain. Until then, dogs remain property, even if they're not furniture, and courts must partition them like land, even when everyone involved knows better.

Sources

Analysis based on Delaware Chancery Court opinions (Callahan v. Nelson), Bloomberg Law reporting, Courthouse News coverage, and comparative state pet custody law research