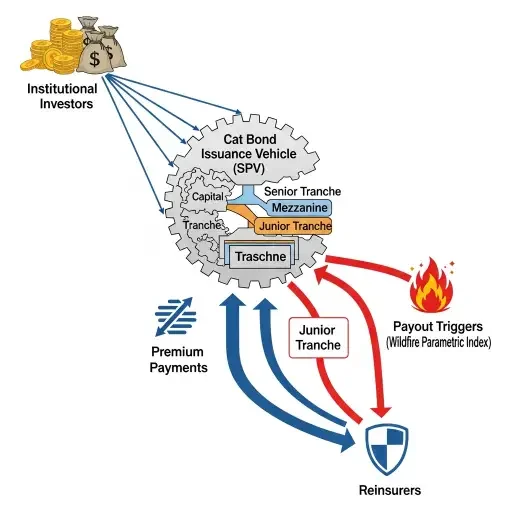

The catastrophe bond market has always trafficked in the improbable—earthquakes that fracture coastlines, hurricanes that erase neighborhoods. These instruments convert existential risk into tradeable securities, letting insurers offload tail events to capital markets hungry for yield uncorrelated with equities. For decades, the logic held: natural disasters were rare enough to model, frequent enough to price. Then climate change rewrote the probability distributions.

Wildfire-linked cat bonds are now the canary in the coal mine—or perhaps the smoke detector in the forest. Issuance has accelerated beyond the actuarial infrastructure designed to value them. The reason is elegant and unsettling: geospatial analytics have made previously unmeasurable risks suddenly quantifiable, but the mathematical frameworks for pricing those risks are still catching up. We can map fuel loads and wind corridors with satellite precision, yet expected loss models struggle to incorporate non-stationary climate variables. The result is a market expanding faster than its epistemological foundation.

The Measurement Problem Becomes Tractable

Traditional catastrophe modeling relied on historical loss data—a century of insurance claims smoothed into probability curves. Wildfires disrupted this approach because their frequency and intensity are changing in real time. A 100-year fire in 2005 is now a 30-year event. Historical data, the bedrock of actuarial science, became a lagging indicator.

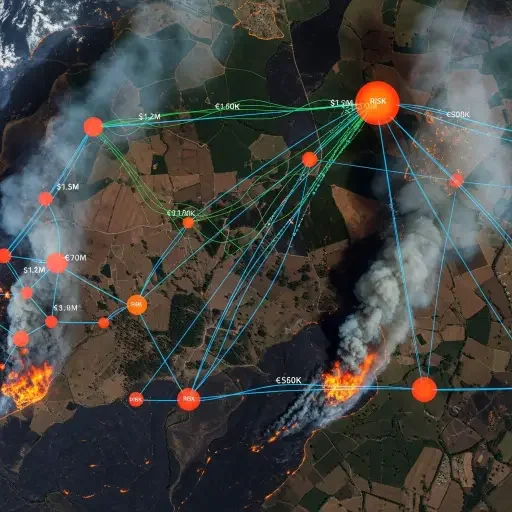

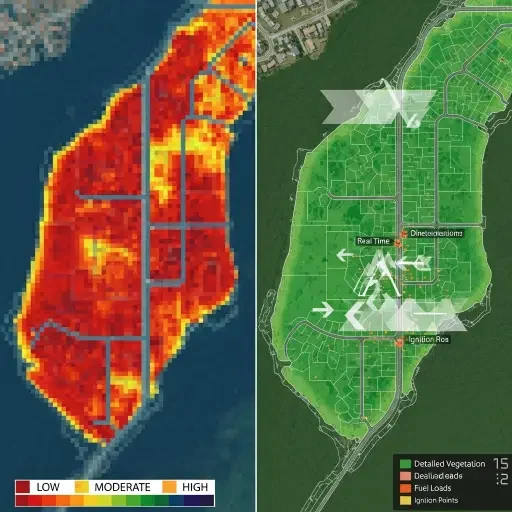

Geospatial technology changed the calculus. High-resolution satellite imagery can now track vegetation density, soil moisture, and topographic channels that funnel wind. Machine learning models ingest decades of remote sensing data to predict fire behavior at the parcel level. What was once a smoothed aggregate—"California wildfire risk"—became granular, addressable, and tradeable. Insurers could finally segment exposure geographically, and capital markets could price that segmentation.

This is not simply better data. It is a category shift in what constitutes knowable risk. When you can measure fuel continuity across a 10-kilometer grid and cross-reference it with historical ignition sources, you transform wildfire from an actuarial abstraction into a computable event. The friction between measurement capability and modeling methodology is where the current tension lives.

Expected Loss Meets Tail Risk Reality

Catastrophe bonds are priced using expected loss frameworks: the probability of an event multiplied by its severity. For earthquakes and hurricanes, this math has decades of validation. For wildfires in a warming climate, the formula requires adaptation. The distribution is no longer stationary—mean and variance are drifting upward. Tail risks, once comfortably beyond the 99th percentile, are migrating toward the center.

Rating agencies face a methodological bind. They must assign credit ratings to instruments whose underlying hazard is evolving faster than the models can recalibrate. A cat bond priced assuming a 2% annual probability of trigger might face a 3.5% probability within its three-year term if drought conditions worsen. The instrument's risk profile shifts mid-flight, but the rating remains fixed unless explicitly revised.

Institutional investors understand this. They are not naive. But they also operate within mandates that require rated securities, and rating agencies are constrained by the need for model stability. The solution, emerging slowly, is dynamic recalibration—updating loss probabilities as new climate data arrives. This is conceptually sound but operationally complex. It means cat bonds become living instruments, their risk profiles updated quarterly rather than set at issuance. Markets can handle complexity, but they demand transparency.

The mathematical accommodation required is straightforward in theory: shift from stationary to time-varying expected loss models. Incorporate climate projections as forward-looking parameters rather than treating them as exogenous shocks. In practice, this demands coordination among modelers, rating agencies, and regulators—entities that move at different speeds and answer to different incentives.

The Demand Curve for Climate-Resilient Capital

Pension funds and sovereign wealth funds are increasingly explicit about climate risk exposure. They want assets that either hedge against climate shocks or provide returns uncorrelated with climate-linked market volatility. Wildfire cat bonds occupy an unusual position: they are climate-exposed by definition, yet they offer protection to insurers who would otherwise face portfolio-threatening losses.

This creates a liquidity puzzle. As climate events grow more frequent, cat bonds pay out more often, reducing their attractiveness to yield-seeking investors. Simultaneously, insurers need these instruments more urgently, driving demand. The equilibrium price rises, but so does the expected loss. The market is functional, but it is not calm.

The institutional response has been bifurcated. Some investors treat wildfire cat bonds as short-duration volatility plays—high yield, high risk, quick turnover. Others view them as long-term hedges within diversified climate portfolios, accepting periodic losses as the cost of uncorrelated returns. Both strategies are rational, but they imply different pricing models and different liquidity expectations.

What is not rational is ignoring the tail risk entirely. Climate-linked cat bonds will experience more frequent trigger events than historical models predict. Investors who price these instruments using pre-2020 loss distributions are underestimating their exposure. The due diligence required is not simply reading a prospectus—it is interrogating the geospatial model, understanding its assumptions about fuel load dynamics, and stress-testing its projections against high-emission climate scenarios.

Friction as Feature, Not Bug

The expansion of wildfire cat bonds ahead of actuarial consensus is not an anomaly—it is how markets absorb new information under uncertainty. Capital flows toward instruments that offer solutions to emerging problems, even when those instruments are imperfectly understood. The friction between issuance pace and modeling rigor is a signal that the market is pricing a risk that regulators and rating agencies have not fully codified.

This friction will persist. Climate risk is non-stationary by nature, which means any actuarial model will be provisional. The goal is not to eliminate uncertainty but to make it transparent and computable. Geospatial analytics provide the measurement layer. Rating agencies must now build the valuation layer that reflects time-varying risk. Investors must demand that transparency and price it accordingly.

The conclusion is not that wildfire cat bonds are mispriced—though some certainly are—but that the infrastructure for pricing them robustly is still under construction. These instruments will continue to grow because the underlying need is acute: insurers cannot hold wildfire risk on their balance sheets indefinitely, and capital markets can absorb volatility that individual firms cannot. But growth without rigorous modeling is speculation dressed as risk transfer.

Climate-linked instruments are the future of catastrophic risk finance. The question is whether that future is built on adaptive, transparent frameworks or on models that lag behind the pace of environmental change. The answer will be written in the loss ratios of the next decade—and in the willingness of market participants to demand better mathematics before deploying more capital.

Sources

Analysis based on insurance-linked securities market data, actuarial literature, rating agency methodologies, and climate finance research.