There's a moment in every technological revolution when the tools stop merely amplifying human capability and start generating something genuinely new. For mathematics, that moment arrived quietly in December 2023, buried in a Nature paper with the unassuming title "Mathematical discoveries from program search with large language models." Google DeepMind had built FunSearch—a system that pairs language models with automated verification—and pointed it at the cap set problem, an open question that had frustrated mathematicians for decades. FunSearch found solutions no human had conceived.

The cap set problem asks: what's the largest collection of points you can place in a high-dimensional grid such that no three points form a straight line? It sounds like geometric trivia, but it represents an entire class of extremal combinatorics problems—questions about maximal configurations under constraints. Terence Tao, one of the world's leading mathematicians, called it his favorite open problem. FunSearch discovered new constructions that pushed the boundaries further than any previous attempt.

This wasn't incremental improvement. This was discovery.

The Architecture of Artificial Creativity

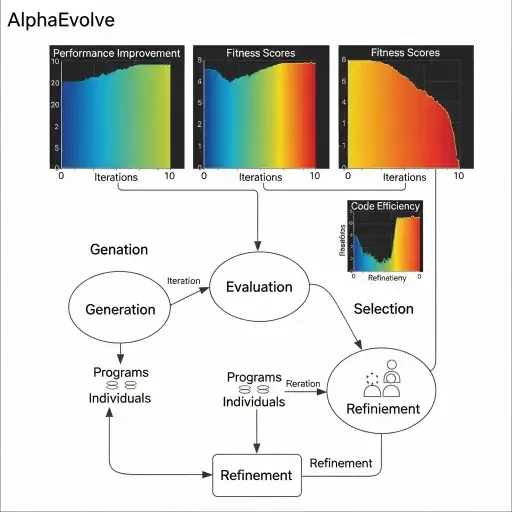

FunSearch works through what might be called computational evolution with a conscience. The system maintains a database of candidate programs—snippets of code that attempt to solve the problem. A large language model examines the best performers and generates variations, mutations that explore nearby regions of the solution space. Each new program runs automatically, gets evaluated against the problem's constraints, and either joins the database or disappears.

The method pairs a pre-trained LLM with an automated evaluator to guard against hallucinations and incorrect ideas, creating an iterative process where initial solutions evolve into new knowledge. The "Fun" in FunSearch doesn't denote entertainment—it stands for "functions," the mathematical objects the system discovers and encodes as executable programs.

This architecture solves a fundamental problem with language models: they hallucinate with confidence. A mathematician's worst nightmare is a plausible-sounding proof with a subtle flaw buried in line 47. FunSearch's evaluator acts as an uncompromising referee, rejecting anything that doesn't actually work. The LLM provides creativity; the evaluator provides rigor. Together, they form something resembling mathematical intuition paired with formal verification.

The system proved its practical value beyond pure mathematics. FunSearch discovered more effective algorithms for the bin-packing problem, which has applications such as making data centers more efficient. This problem—how to pack items of varying sizes into the minimum number of containers—appears everywhere from logistics to cloud computing resource allocation. FunSearch's solutions outperformed decades of human-designed heuristics.

From Functions to Entire Codebases

By May 2025, Google DeepMind had extended the approach dramatically with AlphaEvolve. Where FunSearch discovered individual functions, AlphaEvolve can evolve entire codebases and develop much more complex algorithms, pairing the creative problem-solving capabilities of Gemini models with automated evaluators. The system uses an ensemble approach: Gemini Flash explores breadth, generating diverse possibilities quickly, while Gemini Pro provides depth, offering more sophisticated refinements.

The results cascade through practical systems. AlphaEvolve discovered a heuristic that continuously recovers, on average, 0.7% of Google's worldwide compute resources, a solution now in production for over a year. That might sound modest until you consider the scale—0.7% of Google's infrastructure represents enormous computational capacity, recovered not through new hardware but through smarter scheduling algorithms.

The system reached further into specialized domains. AlphaEvolve proposed a Verilog rewrite that removed unnecessary bits in a key arithmetic circuit for matrix multiplication, a proposal integrated into an upcoming Tensor Processing Unit. It's collaborating with chip designers, suggesting optimizations that passed rigorous verification methods. And in a recursive twist, AlphaEvolve sped up a vital kernel in Gemini's architecture by 23%, leading to a 1% reduction in Gemini's training time—the AI improving the AI that improves the AI.

Proving Theorems with Formal Guarantees

While evolutionary coding agents were rewriting algorithms, a parallel revolution was unfolding in automated theorem proving. The challenge here is different: proving a theorem means constructing an argument so rigorous that every logical step can be verified mechanically. It's not enough to be plausible; it must be absolutely correct.

Princeton's Goedel-Prover-V2 represents the state of the art in open-source theorem proving. The new version improved from 60 percent accuracy on the miniF2F benchmark six months earlier to 90 percent, a dramatic acceleration that surprised even the researchers. The system uses Lean, a programming language that verifies proof correctness, enabling what they call "self-correction mode"—the AI learns to revise its own proofs, iterating toward validity much as humans do.

Then came the International Mathematical Olympiad results. In 2025, multiple AI systems—including one called Aristotle—achieved gold-medal-equivalent performance on IMO problems by combining formal verification with informal reasoning, solving five of six problems with formally verified proofs. These aren't simple arithmetic problems; they're the kind that separate gifted high school students from gold medalists at the world's most prestigious mathematics competition.

The implications ripple outward. Generative AI can almost instantaneously translate proofs into formats that automated systems can verify, while the verification process catches any AI-generated errors or hallucinations. This creates a symbiotic relationship: the language model generates candidate proofs quickly; the formal verifier ensures correctness rigorously. Neither could achieve this alone.

The Data Flywheel and Mathematical Exploration

Mathematician Jordan Ellenberg, who collaborated on FunSearch, captured something essential about these systems. After examining the solutions they generated for the cap set problem, he noted that the programs were "far conceptually richer than a mere list of numbers"—studying them taught him something new about the problem's structure.

This points to a crucial shift: these systems aren't just answering questions; they're generating new questions and approaches. AlphaEvolve demonstrated that LLMs, when carefully guided and their outputs rigorously verified, can be powerful engines for scientific discovery. Applied to more than 50 open mathematical problems, the model rediscovered state-of-the-art solutions 75% of the time and discovered improved solutions 20% of the time, including advances on the kissing number problem—how many spheres can touch a central sphere in n dimensions—which has challenged mathematicians since the 19th century.

The most striking achievement came in matrix multiplication. AlphaEvolve developed an algorithm to multiply two 4×4 complex-valued matrices using 48 scalar multiplications, offering the first improvement after 56 years over Strassen's algorithm in this setting. Strassen's 1969 result was a landmark in algorithmic efficiency; improving on it seemed nearly impossible. AlphaEvolve found a way.

A new implementation of FunSearch released in March 2025 by mathematician Jordan Ellenberg and collaborators made the technology accessible to working mathematicians without machine learning expertise or high-performance computing resources. The system demonstrated that it successfully learns across combinatorial and number-theoretic settings, with principles that sometimes generalize beyond the original training problem.

The Human-AI Research Partnership

These systems aren't replacing mathematicians—they're amplifying them. MIT researchers received grants to build connections between the L-Functions and Modular Forms Database and the Lean4 mathematics library, making billions of unformalized mathematical statements accessible to formal proof systems. This creates a bridge: databases containing computational results from decades of mathematical research can now feed directly into theorem-proving AI, vastly expanding what the systems can discover and verify.

The collaboration extends to problem formulation. Most of AlphaEvolve's mathematical discoveries came from open problems suggested by external mathematicians Javier Gomez Serrano and Terence Tao, who advised on how to best formulate them as inputs. The AI needs human expertise to frame questions properly, while humans benefit from the AI's ability to explore vast solution spaces systematically.

At Harvard, mathematician Michael Brenner witnessed the transformation firsthand. In fall 2023, AI managed to solve only 30-50% of problems in his graduate-level partial differential equations course. By spring 2025, the same models aced the hardest problems. The shift forced a pedagogical rethinking: Brenner eliminated traditional homework, instead having students create increasingly difficult problems to challenge AI systems, generating hundreds of novel problems that now form valuable research data.

Beyond Mathematics: The General Discovery Engine

The architecture underlying these systems—language models generating candidates, automated evaluators ensuring correctness, evolutionary pressure selecting improvements—applies far beyond mathematics. According to Google, AlphaEvolve's general nature means it can be applied to any problem whose solution can be described as an algorithm and automatically verified, potentially transforming areas such as material science, drug discovery, and sustainability.

The constraint is evaluation: you need a way to automatically assess whether a proposed solution works. For mathematical theorems, that's formal verification. For bin-packing, it's testing whether items fit. For circuit design, it's whether the modified circuit maintains functional correctness. But countless problems fit this pattern—protein folding configurations, molecular stability, optimization schedules, resource allocation strategies.

This generality matters because it represents a methodological breakthrough, not just a domain-specific tool. The systems are learning to search solution spaces intelligently, guided by both the broad pattern-matching of language models and the precise constraints of automated verification.

The Philosophical Turn: From Computation to Creation

We're witnessing something unprecedented: machines that don't just calculate but discover. The distinction matters. Calculation executes known procedures; discovery generates new knowledge. For centuries, mathematics has advanced through human insight—recognizing patterns, formulating conjectures, constructing proofs. These AI systems are doing something structurally similar, though through different mechanisms.

The cap set problem result marks a threshold. This represents the first time a new discovery has been made for challenging open problems in science or mathematics using LLMs. Not the first time computers helped mathematics—automated proof checkers and computational exploration tools have existed for decades. But the first time a language-model-based system generated genuinely new mathematical knowledge about an open problem.

The speed of improvement is dizzying. Princeton's theorem prover went from 60% to 90% accuracy in six months. Problems that stumped AI in fall 2023 became trivial by spring 2025. Systems that could barely handle single functions now evolve entire codebases. This isn't linear progress; it's exponential, with each improvement enabling the next.

There's also a recursive element emerging. AlphaEvolve improved the algorithms that train Gemini, which powers AlphaEvolve. Harvard students are creating problem sets that stretch AI capabilities, generating training data that makes the AI stronger. Researchers using AlphaEvolve to discover new mathematics are simultaneously teaching it what kinds of problems mathematicians find interesting. The feedback loops are tightening.

Yet limitations remain sharp. These systems excel at problems with clear evaluation criteria but struggle with the open-ended exploration that characterizes much of mathematical research. They can discover better cap sets but can't formulate new questions about why cap sets matter. They optimize algorithms brilliantly but don't decide which algorithms deserve optimization. The creative spark that identifies important problems still requires human judgment.

The Next Decade: Collaboration or Automation?

Looking forward, the trajectory seems clear: these systems will become standard tools in mathematical research, as fundamental as computer algebra systems or proof assistants. The question isn't whether they'll be used, but how the collaboration will evolve.

One possibility: AI as research assistant, handling verification and exploring solution spaces while humans provide direction and interpretation. Another: AI as co-researcher, proposing questions and approaches that humans might not consider, with genuine back-and-forth collaboration. The most speculative: autonomous mathematical discovery systems that identify important open problems, formulate approaches, and verify results with minimal human intervention.

The infrastructure is developing rapidly. Open-source implementations like OpenEvolve are appearing, democratizing access. Researchers are building bridges between massive mathematical databases and formal theorem provers. Universities are rethinking mathematics education to account for AI capabilities. The ecosystem is forming around these tools.

What remains constant is the need for verification. Mathematics demands certainty, and the architecture that pairs creative generation with rigorous evaluation provides exactly that. It's this combination—the wild exploration of language models tamed by the unforgiving precision of formal verification—that makes these systems reliable enough for mathematical discovery.

The automated mathematician has arrived, not to replace human mathematicians but to expand what's possible. Problems that would require lifetimes of human calculation can now be explored computationally. Algorithms that seemed optimal for half a century can be improved. Theorems that eluded proof can be verified formally. The pace of mathematical discovery, limited for centuries by the speed of human thought, is accelerating into new territory.

And we're only at the beginning—FunSearch and AlphaEvolve represent first attempts at a fundamentally new kind of mathematical tool. As language models improve, as verification systems become more sophisticated, as the integration between creative generation and rigorous checking deepens, these systems will tackle problems of increasing difficulty and importance. The question mathematicians now face isn't whether to use these tools, but how to use them most effectively to push the boundaries of human knowledge further than ever before.

Sources

Google DeepMind technical reports, Nature publication on FunSearch, arXiv preprints on AlphaEvolve and mathematical discovery, academic papers on automated theorem proving